Bardolph was in his room feeding pheasant’s intestines to his peregrines when a rap came upon the door. At first he considered this to be the arrival of the lad Ralph, but quickly changed his mind. To visit Onneyditch and return was a good two hours journey and barely an hour had passed. This had to be the serving maid with the jug of water he had ordered. ‘You may enter,’ he called.

Bardolph had his back to the door when the rap came and saw no reason to look around. However when the door swung open noisily he immediately moved a hand to his dagger. His keen senses told him this was not the entrance of a serving maid. Quickly he turned to confront the visitor. A burly soldier with ruddy face, an unruly shock of unkempt red hair, and a large bulbous nose took one pace into his room and banged the door shut behind him. All the man’s actions appeared heavy and clumsy. There was no helmet to his head and his chain-mail hood was down about his shoulders, but he was attired in the distinctive dark-blue and red halved tunic of the de Clancey’s along with the three rampant white lions of Lodelowe emblazoned upon his chest. Two twisted bright red tassels, one to each lapel, indicated this to be a man of senior rank, and most likely the castle’s Sergeant-at-Arms, a position that ranked one below that of Captain Osbald. Slowly Bardolph’s hand relaxed from his dagger and moved to his side.

The Sergeant stood rigidly to attention. He cleared his throat before speaking. ‘Sire, my name is Cuthred,’ he told the Falconer, ‘Sergeant-at-Arms to Lodelowe and the Baron de Clancey. Captain Osbald regrets that he cannot join you at this hour. He has other duties to perform. He therefore sends me to ask if there is anything you so desire? I have instructions to ensure that your every need is met.’

Bardolph was well aware of Captain Osbald’s duties and why he could not attend in person. However he gave the question of need some thought. He concluded there was not a great deal he wanted. His birds were well fed and the lad Ralph, even though he had not yet arrived, was in all probability well on his way to the castle. Furthermore his horse and donkey were stabled and being well looked after. He looked about the chamber. He had clean linen on his bed, and the room was warm and well aired. He could think of nothing he so desired. Then a thought occurred to him. The name Sergeant Cuthred triggered something in his mind. He recalled something Captain Osbald had said about how he and Sergeant Cuthred being present at the search of the handmaiden. At the time he had not had time to question Captain Osbald further, so he was thinking perhaps his second in command might enlighten him with details of what actually happened.

He addressed the Sergeant. ‘There is something you can do Sergeant,’ he told him. ‘Tell me what you know about the forthcoming trial of the handmaiden? Tell me about the search and the signet ring, and what part you did’st play in finding it?’

Sergeant Cuthred looked a little surprised but had no objections and was fully prepared to reveal what little he knew. ‘Sire, both the Captain and my good self did’st conduct the search of the handmaiden in her cell. The ring was found concealed upon her person. It was hidden within the heel of one of her shoes,’ he explained.

Bardolph rubbed his chin thoughtfully. Curiosity was getting the better of him. He recalled the handmaiden’s shoes she had been wearing that day at the ford. If he was not mistaken they were of Norman origin and very similar to those worn by the Lady Adela. ‘What else can you tell me Sergeant?’ he asked. ‘Was anything else found? What of the trial? Who stands in judgement alongside me?’

The Sergeant shook his head and attempted to answer the questions in the order they came. ‘Sire, only the ring was found upon the handmaiden,’ he replied and answering the Falconer’s first question. This he could do, but as regards the rest, these were subjects he knew nothing about. He therefore continued by saying; ‘There is nothing else I can add Sire. That is all I know. Other than being present at the search, I have no other involvement. I know nothing of the forthcoming trial or who stands in judgement other than it is scheduled for the morrow. Such things are organised by the Baron.’

Bardolph turned pensive. The Sergeant was just a minnow of the Baron and he did not expect any more from him. However he remained curious and he had an idea. After giving the subject much thought, he asked; ‘Sergeant, you say you have been given instructions to ensure that my every need is met?’

‘Those were my instructions Sire,’ he confirmed.

‘Everything?’ added Bardolph.

‘Everything Sire,’ assured the Sergeant.

Bardolph smiled. His curiosity was now greater than ever and he wanted to learn more. But obviously this would not come from this man. He decided on a change of voice and addressed the Sergeant speaking as a superior; the tone of his voice suggesting that of a man in charge. ‘Sergeant, there is one thing you can do for me,’ he said. ‘You will’st take me to see the prisoner whose trial I attend on the morrow.’

Sergeant Cuthred hesitated even though it appeared to be a direct order. The Falconer’s request was irregular and had come as a complete surprise. However the Sergeant’s orders were explicit. He had been despatched with instructions to ensure that this man’s every need be met. He turned towards the door. He was a soldier and obeying orders was what he understood best. ‘Pray accompany me Sire,’ he said. ‘I will’st escort you to the dungeon.’

Bardolph slung a cape about his shoulders and skilfully positioned his feathered hat to the side of his head. ‘I am ready,’ he said. ‘Lead the way Sergeant.’

Walking side-by-side, Sergeant Cuthred and Bardolph traversed the main courtyard, their destination the castle’s keep. On arrival at the keep and with the doors closed behind them, the two men waited for their eyes to acclimatise. What little light existed came from two narrow slits positioned high and to either side of the big entrance doors.

Bardolph peered into the gloom, and as his eyes adjusted he found himself standing in a vast empty hall. Nothing existed, no refineries and no decorations. There was a long table almost the width of the hall, but this was pushed back against the far wall. To the right stood a large inglenook fireplace and on the hearth there rested a brazier and bellows. It was not lit. Other than these items all that existed were plain walls and a damp flagstone floor.

After a short pause Sergeant Cuthred moved off through a door to the left, and leading the way along a series of long dark passages before descending many stairs before coming to an abrupt halt before a small arched and gated iron portal. A lone soldier stood guard. The soldier, with one large key attached to a chain and anchored to his belt, turned the lock and allowed the two men to step through to the other side.

Immediately beyond lay a stone staircase that spiralled down into the blackness of the castle’s dungeon. Sergeant Cuthred took three steps down then turned to check that Bardolph accompanied him. Bardolph nodded and the two men began their perilous descent. There was a burning torch about halfway down, but for most of the descent the stairs remained in total darkness. It was only the even pacing of the steps and the ever presence of the endlessly curving outer wall that kept Bardolph dropping at a steady, mechanical pace.

A second gate placed before the final step blocked the stairwell at the bottom. A guard on the other side unlocked the gate and stood rigidly to attention as the two men stepped through onto the uneven flagstones beyond. For a while they tarried whilst Sergeant Cuthred talked briefly about security to the guard. Bardolph took the opportunity to look about him. He had arrived at one end of a long, low arched corridor, dimly lit by a scattering of blazing torches placed in brackets and spaced at irregular intervals down the distant length of the passageway.

They set off again with Sergeant Cuthred leading the way. In the middle of the passageway there stood a table. On it rested a pile of clothes. Bardolph moved to view the items. On display was a long green frock with one sleeve hanging loose, a white singlet undergarment, a plain white bonnet, a small wooden cross on a short leather thong, and a pair of ladies shoes: He recognised the items: These were the clothes of the handmaiden, torn and stained by the journey from the ford.

A small balding man appeared carrying chains and manacles. Sergeant Cuthred introduced him to Bardolph. ‘Sire, this is Barik the castle’s jailer,’ he said. ‘He keeps a goodly dungeon here and applies his trade with diligence.’ Then turning to Barik, he explained; ‘And this is Bardolph, Royal Falconer to the King of England. He sits in judgement on the morrow at the trial of the handmaiden.’

Bardolph gave a slight nod of recognition and pointed to the pile of clothes on the table. ‘These items are those of the handmaiden are they not?’ he queried, even though the question was rhetorical, for he was well aware of their ownership.

Barik nodded his head. ‘Aye Sire, they are,’ he replied. ‘They are the clothes of the handmaiden. They are to be presented as evidence at her trial.’ Bardolph turned to Sergeant Cuthred.

‘May I take a look?’ he asked. ‘May I be permitted to examine the evidence in advance of the trial?’

Sergeant Cuthred saw no reason to oppose the request. The Falconer would be presented with them on the morrow anyway.

‘Aye Sire, pray carry on,’ he said.

Bardolph fingered the material of the dress then moved on to pick up the shoes. He looked them over. The shoes were of Norman origin, most certainly cobbled in France and of the finest quality. The bases were of carved oak, the uppers shaped from soft tanned leather, and the edges surrounded by big brass studs, hammered home to seal and waterproof the uppers to the base. The heels suggested little wear despite the mud. Bardolph concluded that these shoes had hardly been worn.

Sensing something loose, Bardolph raised the shoes to an ear and shook them vigorously. One shoe rattled and he decided to investigate. He placed a finger within the heel and raised the thick leather inner lining. The wooden base beneath had been hollowed to create a small secret compartment. Inside was a small object wrapped untidily in a torn piece of yellowed and stained parchment paper. Bardolph knocked out the contents and returned the shoe to the table. He then carefully unravelled the parchment. On opening he discovered a solid-gold signet ring, the face engraved with a vertical stripe and the three rampant lions of Lodelowe set within a shield.

Bardolph turned to Sergeant Cuthred and showed him the face of the ring. ‘Is this the seal of the House of Lodelowe?’

Sergeant Cuthred nodded his head. 'Aye Sire it is the signet ring of the late Baron Edward de Clancey. His legacy was locked within the castle’s strongroom. This ring was stolen from there some three weeks past.’

Bardolph remained curious and furrowed his brow. ‘Is this how the ring was found?’ he asked. ‘Wrapped and concealed within the heel of this shoe, just as I see it now?’

Sergeant Cuthred nodded his head. ‘Aye Sire it was,’ he responded, ‘and no evidence has been tampered with. Those were my strict instructions. You see the ring exactly as it was found.’

Bardolph continued with his questioning. ‘Who conducted the search? Was it just you and Captain Osbald?’

Sergeant Cuthred answered immediately since he had nothing to hide. ‘It was Sire,’ he revealed, ‘I did’st assist in the search along with Captain Osbald. No one else was there. Together we did’st search the handmaiden, and it was I that pointed out the secret compartment to the Captain.’

Bardolph’s face turned quizzical. ‘So you knew beforehand of these secret compartments?’ he said. ‘Pray tell me Sergeant, just how might this be?’

Sergeant Cuthred was quick to answer. ‘Sire, I had earlier searched the contents of the cart,’ he explained. ‘There were many shoes amongst the luggage and all had heels shaped in the same fashion. So when the turn came to search the handmaiden I was well aware of the cobbler’s craft.’

Bardolph stroked his beard. ‘I see,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘So pray tell me Sergeant, was anything else found upon the cart?’

Sergeant Cuthred shook his head. ‘Nay, nothing else Sire,’ he said, ‘nothing more was found, neither within the shoes nor amongst the rest of the luggage. Both the cart and Lady Adela’s person were clean. Only the handmaiden was found to be concealing anything that did’st not belong to her.’

Bardolph held the offending ring high and pointed to the shoe on the table. ‘Then only this ring was found, and discovered by both you and Captain Osbald?’

Sergeant Cuthred nodded his head. ‘That is correct Sire,’ he confirmed, ‘nothing else was found.’

Bardolph considered the matter before continuing with his questioning. ‘Then pray tell me Sergeant,’ he asked next, ‘what did the handmaiden say when the ring was presented to her?’

Sergeant Cuthred shrugged his shoulders and thought back to the time when Captain Osbald presented the ring to the handmaiden. ‘The handmaiden denied all knowledge of it,’ he said coldly.

Bardolph frowned and gave a look that suggested incredulity, for the rattle within the heel was most evident. ‘And she offered you no explanation?’ he quizzed.

Sergeant Cuthred shook his head. ‘Nothing that held credence Sire, just feeble excuses,’ he said. ‘She spoke of the shoes being handed to her by Lady Adela for the journey, and if prior to this any objects had been placed within the heels, then she bore no knowledge of them.’

Bardolph frowned. ‘And you do not believe her story?’ he suggested. ‘Could the handmaiden not be speaking the truth?’

‘I think not Sire,’ answered Sergeant Cuthred scornfully. ‘When challenged the handmaiden did’st merely repeated what she had been told to say. It is of my opinion she was always aware of the ring’s presence.’

Bardolph looked to the shoes and scratched his head. ‘But Sergeant,’ he said and sounding sceptical, ‘I remain puzzled! Surely if the handmaiden knew of the ring’s presence, then why did she not try to get rid of the evidence long before the search took place? This ring is small, it could be hidden anywhere, even in her cell there would be cracks to the walls where such damning evidence could be concealed and never traced.’

Sergeant Cuthred laughed a hearty roar for he was now on much safer ground. ‘Sire, the handmaiden remained with her hands bound from the time of her arrest to the time of the search. A fortunate happening no doubt, for what you hypothesise could very well have happened and we would not now be gathered here to debate upon such matters.’

Bardolph gave a wry smile. This was not the answer he was expecting, but he could see it all now. The only logical conclusion was that the girl was lying for her mistress. However he made no comment, instead he turned his attentions to the wrapping. Someone had torn away a corner of a manuscript for the purpose. There were traces of writing in faded but very distinctive light-blue ink, but it had become rubbed and smudged, and too blurred to decipher. He turned the ring over in his hand before re-wrapping it carefully, using the same folds, and placing it back in the heel of the shoe. He then shook the shoe vigorously so that the Sergeant should once again be reminded of the rattle.

‘Was there no other packing inside?’ he asked. ‘Is this exactly how the shoe was found?’

Sergeant Cuthred nodded his head. ‘This is exactly how the shoe was found Sire,’ he confirmed.

Bardolph did not speak. It seemed hard to believe that the handmaiden had worn these shoes for at least two days and not sensed something loose within the heel. He had noticed it straightaway. After pondering for a little while longer he decided to put no further questions. He would save them for the morrow at the trial of the handmaiden.

As Bardolph pondered and stroked his beard, Barik rattled the chains held in his hands. The Falconer turned to face the jailer. ‘What is it?’ he asked.

Barik sounding apologetic explained the reason for his ill-mannered interruption. ‘Sire, if I may be permitted to take my leave, I have much work to do,’ he said. ‘The handmaiden is to be prepared for her trail. These shackles must be applied to her person before she stands before the court.’

Bardolph understood and nodded his head. It was never his intention to interrupt the workings of the castle’s dungeon. ‘Pray do what must be done,’ he said. ‘It is I that meddle in your affairs, and for this I must ask of your pardon.’

Barik bowed and took his leave gracefully. Bardolph watched him go. A whistle signalled a guard to accompany him; then with chains slung over one shoulder he set off at a brisk pace for a gated portal sited at the far end of the long passageway.

Bardolph turned to Sergeant Cuthred. ‘Tell me Sergeant, what does’t now happen?’ he enquired. ‘What fate now awaits the handmaiden?’

‘A forge and anvil lie within the chamber beyond,’ the Sergeant explained; ‘The handmaiden will be shackled for her trial. It is practice of Ludlow and of all the Marches that prisoners standing trial be shackled hand and foot.’

Bardolph was of the opinion that shackles were unnecessary. But he nodded his head in acknowledgement. Invariably ancient Dane Law still applied within many regions and its tradition went back centuries. He shook his head in sadness and sighed deeply. Dungeons and their workings were not of his liking. He felt very much out of place down here. He was a man of the forest and the open skies.

Bardolph turned to leave. His birds were left unattended and as yet the lad Ralph had not arrived. He was about to walk away when a scream from a nearby cell attracted his attention. He looked around to see a guard manhandling the handmaiden out of her cell. A push from behind had sent her tumbling to the floor. To begin with she had a blanket about her, but it slipped from her grasp as she fell. With one hand beneath an arm the guard lifted her to her feet and marched her swiftly towards the far portal. On being raised to her feet she made a grab for the blanket but failed in her grasp. As a result the blanket remained on the floor next to her cell.

As the guard and handmaiden passed by, Bardolph turned, and at a few paces distance pursued them down the passageway. Sergeant Cuthred, a little surprised by the sudden turn of events, followed swiftly on Bardolph’s heels.

Bardolph had no intention of giving up the pursuit and followed the guard and handmaiden through the low portal. On the other side he stood erect and looked about him. He was now in a large chamber with high vaulted ceiling and rows of square stone pillar supports. There were no windows and light came from candles banked on iron stands.

The chamber was warm, heated by a furnace placed beneath a ventilation shaft to one corner. Bardolph still shuddered uncomfortably, for the gruesome sights that lay about him were chilling to the bone. This was a chamber of torture, with many devices placed about the floor. There was an abundance of chains, many fixed to pillars and walls, whilst others hung down from the high vaulted roof.

Sergeant Cuthred followed Bardolph through the portal and deliberately positioned himself between Bardolph and the furnace. ‘Pray good Sire,’ he said. ‘Do not venture too close to the coals, for they spit sparks and may damage your clothes. It would also be wise to stand back and let the jailer do his work. Unnecessary movement from the handmaiden when the hammer falls could result in much distress. The strike must be swift and sure.’

Bardolph understood. Sergeant Cuthred was no fool and was speaking from experience. He nodded his head in recognition. ‘With your permission I will’st remain here and observe from the portal,’ he said. ‘It was never my intention to interfere.’

Sergeant Cuthred moved to stand alongside Bardolph. ‘Then Sire, together we will observe from this safe distance,’ he said.

Four hot rivets glowed in the coals, and the handmaiden, held by the guard, stood nervously alongside an anvil. Barik turned the rivets over in the flames, and as sparks flew he signalled that he was ready.

The guard placed an iron band about the handmaiden’s wrist and she was made to kneel beside the anvil. It was now the turn of the jailer. Held by tongs and at arms length, he carried a red-hot rivet to the anvil. He placed the rivet within the flanges of the shackle then raised a hammer. The handmaiden had been prior warned not to move, but as the hammer fell she winced all the same, and three strikes were necessary before the rivet was hammered home.

The handmaiden screamed as heat from the rivet made contact with the skin. However the remedy was simple. A pail of water alongside the anvil lay in readiness. The guard thrust the wrist deep within the water and immediately a jet of steam hissed upwards from the bucket.

Whilst the shackle cooled a second band of iron was placed about the handmaiden’s other wrist, both bands being connected by a short chain. The riveting operation was then repeated. On this occasion the handmaiden kept perfectly still and only one solid strike from the hammer was necessary. Quick to learn, and as soon as the deed was done, she moved her hand to the bucket and thrust it deep in the water.

The shackles consisted of four bands of iron and three chains. Two short chains passed between the wrists and ankles, and a slightly longer one, linked centrally, joined the hands to the feet.

It was now the turn of the feet. A band of iron was passed about an ankle and the foot placed upon the anvil. The handmaiden tried hard to maintain her balance. As the hammer fell she teetered and once more three strikes were needed before the rivet held. She screamed, this time with pain as her ankle turned within the band of iron. Then, as the first pang of agony died away, the searing heat from the rivet touched her flesh and she moved quickly. Hobbling and hopping on one foot, and without assistance, she reached the bucket and placed her foot inside. Stream rose as she tried to catch her breath.

The final band of iron proved the most difficult since the chain that linked the handmaiden’s feet was short. But Barik and his assistant were well experienced in such matters and had done this many times. Whilst the guard held the handmaiden steady, and with one foot resting upon the anvil, Barik completed the task. On this occasion two blows were needed.

As the handmaiden screamed, the guard carried her from the anvil and lowered her foot into the bucket. She stood with the other foot raised and waited for the water to stop bubbling. With chest heaving from the ordeal she began to sob. She wanted to raise her hands and rub away the tears from her eyes, but the chain that linked her wrists to her feet prevented her from doing so. They had shackled her hand and foot, and the short chain allowed no hand movement higher than the waist.

Bardolph decided he had seen enough. He turned to Sergeant Cuthred. ‘Come Sergeant let us depart,’ he said. ‘I have seen enough of this unpleasantness.’

Sergeant Cuthred nodded his head. ‘Aye Sire, these matters are indeed unpleasant, but alas must be done,’ he agreed. ‘Let us not forget that this wench did’st kill and steal from the Baron de Clancey, and for this we must hold no quarter.’

Bardolph said no more and headed for the portal at the foot of the spiral stairs. He felt sorry for the young handmaiden. It seemed that her guilt had already been decided. However, if he could help he would. Perhaps at her trial on the morrow he would get a little closer to learning the truth.

Chapter Seventeen

The trial of the handmaiden was to be held in the castle’s keep. This was not unusual as most trials for the peasantry were held here. The official line being that it was for the convenience of transporting prisoners from the dungeon below, but everyone knew the real reason was to have hot irons present at the trail should the prisoner become obstinate and need a little prompting, or simply as a punishment for their crime. As in the case of thieves who would invariably receive a brand to the forehead. It was for this reason a permanent brazier and bellows rested beneath a wide inglenook chimney to one side of the entrance hall.

Bardolph was last to arrive, escorted by Sergeant Cuthred. Bardolph refused to be rushed. The lad Ralph, who had arrived the night before, needed to be instructed in the ways of caring for two very precious peregrine falcons. Only when Bardolph was totally satisfied that his birds could be left in safe hands did he venture from his room and make his way to the keep.

A large crowd was gathered outside. Normally those waiting would be the privileged few, either by invitation or those that could afford entrance, but on this occasion no fee was asked. Baron de Clancey had been deliberate in his choosing and left nothing to chance. He wanted as many people as possible to attend. It was important that rumours spread quickly throughout the entire length and breadth of the Marches. This way, by granting free admission, the outcome of the trial would become common knowledge long before the arrival of anyone from Salopsbury.

Bardolph entered the castle’s keep and looked about the vast entrance hall. The sight that greeted him was certainly not expected. He had passed this way the day before and had encountered nothing but a vast empty space. But now all was changed. The long table that rested against the back wall had been brought forward and behind now stood a row of ornately carved high-backed chairs. There were seven in total. The hall itself was brightly lit. Hundreds of candles blazed upon the table and torches flared in brackets about the walls. Light also came from a brightly glowing brazier that rested beneath a large open inglenook fireplace. Barik the jailer was stood alongside occasionally pumping bellows and poking the coals.

Six men stood behind the long table. Five were debating in a group, the sixth stood remote and at several paces distance. The group of five were busy pawing over items of clothing laid out upon the surface of the table. All appeared oblivious to the arrival of Bardolph. Only the man stood remote noted his coming, but said nothing and simply stared blankly at his approach.

Of the six men to the rear of the table, only one was know to Bardolph. This was Captain Osbald. Of the remaining five however it was not difficult to place any of them, if not by rank then by standing amongst the community. A man at the very centre of the group, aged about fifty, with well-trimmed beard and cape about his shoulders had to be Baron de Clancey. His action and demeanour exhumed complete authority.

Of the others Bardolph began to categorise them accordingly. He started with the man stood remote from the group. He was most certainly a scribe. He stood with escritoire, a great number of scrolls, an inkwell and several quills before him. He was tall, thin and of almost skeletal appearance, with pale drawn yellow skin and dark sunken sockets for his eyes. He was dressed in a white robe and a black bonnet with ties hanging down before him.

With the Baron, the Scribe and Captain Osbald identified, Bardolph turned his attention to the identifying the remaining three. Most obvious of the three was a man of the cloth, an Abbot by all accounts, for he wore a white habit with black hood, and in his hands he clutched a bible and a crucifix. This man was excessively overweight, with a great protruding belly and sagging jowls. His hood was down, and from the top of his head shone a brightly cropped tonsure of almost pure white. On every finger he wore a ring, some of plain gold, others studded with emeralds and rubies.

With two more men to categorise, Bardolph moved his attention to what appeared to be the youngest member of the group. By his demeanour and attire he could only assume this youth to be of minor nobility, possibly the son of an Earl or Baron. He was young, in his early teens and not yet shaven. But for all his tender years he exhumed an air of authority. He was dressed in the finest silk robes and about his shoulders draped a heavy cloak hemmed in pean.

The final dignitary of the group proved the most difficult to categorise. He was undoubtedly a man of wealth, for he was dressed in the finest attire, all highly decorated and in matching royal blue. He was rotund, though nowhere near the size of the Abbot. He sported a finely trimmed greying beard, a flat cloth hat and in one hand held a long staff topped with a silver orb. He was a man of ageing years, probably in his mid-sixties, and most definitely the oldest person amongst this gathering of Lodelowe’s elite.

Baron de Clancey stood with his back to Bardolph as he entered. But the instant he heard footsteps he turned. ‘Ah, at last my court is complete!’ he remarked. ‘Come, join us good Sire, for we are eager to begin.’

Bardolph walked around the table to join those gathered to the rear of the hall. The Baron held out his hand in greeting. The two men shook hands. ‘Welcome to my court,’ said the Baron. ‘It is indeed a great privilege and honour to have a servant of the King grace our presence this day.’

Bardolph acknowledged the greeting with a polite bow. ‘Likewise my Liege,’ he said; ‘it is indeed an honour and a privilege for me to be here today.’

The time for introductions had come. The Baron moved firstly to the man of the cloth. ‘May I introduce you to the Father Monticelli, the Abbot of Wistanstow,’ he said. ‘He heads a religious order that lies to the north of Onneyditch and a place you must have passed on your journey south. The Abbot’s presence at my court is two fold. One, I ask him to judge, for his opinions and knowledge of the law are held in high esteem: And two, I ask him to oversee the spiritual side of the proceedings, for it is imperative that we get a written confession from the wench today. She must be made to disclose all she knows concerning the robbery. But if she is not forthcoming and proves none co-operative, then I am sure his blessings will come as welcome relief.’

Bardolph dropped to one knee. The Abbot placed a hand upon his head and recited a little prayer in Latin, and on conclusion all those present voiced; ‘Amen’.

As Bardolph rose the Baron turned to the youngest member of the group. ‘Next may I introduce you to Edwin,’ he said, ‘son of Earl de Mortimer, Lord of Powys, High Sheriff of Shropshire and Overlord of the Council of the Marches.’

Bardolph took the young man’s hand and bent low in respect. ‘Greetings Edwin, son of Earl de Mortimer,’ he said, sounding humble.

Edwin acknowledged with a nod to the head. ‘It is indeed a great pleasure and privilege to sit in judgement alongside a servant of the King,’ he said and sounding equally humble.

The Baron moved on. Time was pressing. He was aware that Bardolph had already met Captain Osbald so he passed him by, simply uttering; ‘Captain Osbald you already know.’

Only one man remained to be introduced. This was the man of wealth. ‘Finally may I introduce you to Squire Henry Stokes,’ said the Baron; ‘once servant to a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Squire Henry graces my court with his presence as a fine and upstanding gentleman, not only here in Lodelowe, but across the entire length and breadth of the Marches.’

Bardolph offered the Squire his hand and bowed his head. With the Squire’s cloak partially opened Bardolph noted the cross of St. John of Jerusalem upon his left breast. The two gentlemen shook hands.

‘It is a privilege to be by your side,’ said the Squire.

‘And me by yours,’ said Bardolph returning the complement.

With all formalities over Baron de Clancey clapped his hands to gain attention. ‘Gentlemen, let us begin,’ he said. ‘God willing we will see justice done this day.’

‘Praise be to God that he gives us strength,’ chanted the Abbot in response.

The Baron knelt and clasped his hands in prayer. ‘Let us pray to God for strength,’ he said. ‘Let us pray for guidance. Come, let us all kneel in prayer.’ Bardolph knelt, as did the others: The Abbot added his own blessings to the ceremony by reciting several verses of Latin and culminating in the Lord’s Prayer. When he was done the Baron rose and straightened his tunic.

‘Gentlemen, we have much work to do,’ he said. ‘The trial must begin forthwith. So may I ask of you all to take your seats.’

He then turned to Sergeant Cuthred and added; ‘Sergeant, bring forth the accused, and open the doors to the hall so that the good people of Lodelowe may enter.’

The Baron took his place behind the table, sitting in the middle chair of the row of seven, the table being so arranged that it faced directly towards the doors through which the awaiting crowd would enter.

To the Baron’s right the scribe had already arranged his escritoire and waited alongside his chair. Moving quickly the young nobleman took the vacant chair to the Baron’s left. It seemed rank was important and a seat next to the Baron an effective way of displaying his status.

With the three central positions taken, the Abbot settled his huge bulk down on the side of the Scribe, and Squire Henry Stokes moved to sit next to the young Edwin de Mortimer.

The two men left standing, Bardolph and Captain Osbald, looked to each other then moved to sit at opposite ends of the long table, Bardolph positioning himself next to the Abbot and Captain Osbald alongside Squire Henry Stokes. Bardolph found himself seated behind the pile of clothing.

Whilst the seating arrangement was underway the doors to the hall were opened and those waiting outside entered. They were to stand to the rear, held back by a row of guards. For a while there was shuffling and murmuring, but soon silence fell and the court waited patiently for the accused to appear. The rattle of chains announced the appearance of the handmaiden. From a side door she shuffled slowly into the hall. A heavy blanket draped about her shoulders and dragging the floor hid the fact that beneath she was naked and shackled hand and foot. On entering she hesitated briefly and looked about the room. She had not expected to see people. Not this many anyway.

Sergeant Cuthred urged her forward with the flat palm of an open gauntlet. She stumbled on her chains, caught her balance and moved on. To be truthful she was at a loss as to exactly what was expected of her. She had been told nothing of her trial, or of what to do or say, since no one was prepared to defend her. Sergeant Cuthred continued to push her forward, guiding her towards the centre the floor then called a halt. Here he turned her around to face the table.

A hushed silence befell the hall. The Baron on sensing the earnestness added further solemnity to the occasion by pausing several seconds longer than necessary before raising a silent finger and signalling to the Abbot to begin proceedings with a blessing and a prayer.

The man of the cloth rose awkwardly from his chair, propped his paunch over the edge of the table and addressed Gwyneth across the wide surface. ‘Prisoner, kneel down before us,’ he told her at a chant, ‘so that we may all pray together and ask God to give us strength.’

Still clutching doggedly to her blanket, and with movements restricted by the shackles, Gwyneth sank slowly to her knees and lowered her head. The Abbot, biding his time, recited several long verses in Latin before finally making the sign of the cross before his body and retaking his seat. At a loss as to what to do next, Gwyneth remained on her knees, her head bowed.

The Baron’s voice broke the silence. ‘Will the accused please rise and stand before this court?’ he said loudly so that those at the back could hear.

Gwyneth looked up to see the Baron’s steely eyes glaring across the table towards her. She rose awkwardly, but determined not to release the blanket. Turning her head from side to side she looked along the row at seven stern faces seated behind the great table. She recognised two of the seven. They were sat at opposite ends. One was the Captain she loathed and despised. The other was the man that had shot an arrow and killed one of her escorts. He had been kind to her at the stables when he cut her down and allowed her to rest upon the straw. But this did not make up for his evil deed at the ford, and she concluded that she despised him too.

A hush settled upon the court. The Baron’s stentorian voice cut the silence. ‘Scribe, hand me the charges,’ he said and holding out a hand.

The thin skeleton framed man, forever silent, handed over a scroll. The Baron unfurled it, and holding it out before him proceeded to read the contents. ‘Gwyneth, daughter of Thomas the Fletcher of Salopsbury,’ he started, ‘serving wench and handmaiden to the Lady Adela Fitzgerald, you stand before this court this day accused of robbery and murder, in so much that on the fifth day of August, in the Year of Our Lord Twelve Hundred and Thirty-five, you did aid and abet in the theft of property from his lordship the Baron de Clancey and also did aid and abet in the murder of Richard, son of Frederick, guard to the Baron de Clancey, and thereafter did wilfully partake in the concealment of stolen property from their rightful owner.’

Then, looking up and addressing the accused, he asked directly; ‘Gwyneth, daughter of Thomas the Fletcher of Salopsbury, how does’t you plead to these charges? Guilty or not guilty?’

Gwyneth was lost for words. Surely they did not mean her? She had done nothing. With furrowed brow she stood staring numbly back at the Baron whilst she gathered her wits. These charges were all new to her. She had not been told anything beforehand, either of the accusations, or what to reply. Since the search in her cell, and the ignominy of having the shackles cast about her person, she had neither seen nor spoken to anyone.

Gwyneth took a deep breath and gave her response. ‘Not guilty Sire!’ she replied in a clear and loud voice.

The Baron frowned and drummed his fingers upon the table. ‘Then you do not confess to the charges laid before you?’ he asked and holding up the unfurled scroll for her to see.

Even if from this distance she could see what was written on the parchment, it would have done the court no good, for she could neither read nor write. However, the gesture was simple enough for her to understand and she knew exactly how to respond, for although illiterate she was no fool. Knowing only too well that to admit to robbery and murder meant certain death.

‘No Sire, I cannot confess. For I am innocent of all crimes,’ she replied in a clear and purposeful voice.

The Baron drummed his fingers hard upon the table. ‘Record her words Scribe,’ he growled. ‘The accused denies the charges in the first instance,’ Then returning his attention towards the handmaiden he spelled out clearly the consequences of her denial.

‘By the laws of Lodelowe,’ he began to explain; ‘and of the Council of the Marches, this court can allow you but two more chances to freely admit your guilt. Plead guilty now and reveal to us your knowledge surrounding the robbery and you may depart from this court unharmed. This much I promise. But continue to refuse, and I warn you, that before this day is out this court will have the truth extracted from your lips, so help me God. So I ask you for a second time, Gwyneth, daughter of Thomas the Fletcher, how do you plead to these charges? Guilty or not guilty?’

Gwyneth stood her ground, determined not to give in. ‘Not guilty Sire,’ she replied in an equally loud and purposeful voice.

The Baron thumped the table. ‘Scribe,’ he growled, ‘record this wench’s second denial. This court’s patience grows thin and me thinks she be reminded that more forceful measures be needed in order to gain the confession we so desire. Sergeant, move the accused closer to the table and relieve her of the blanket.’

Sergeant Cuthred stepped forward, placed his hands upon Gwyneth’s shoulders and tugged at the blanket. Doggedly she clung on, fighting for possession, but the Sergeant’s superior strength proved too much and the blanket slipped from her shoulders. Standing naked, she was pushed forward two paces.

As Sergeant Cuthred stepped back a pace the Baron gestured to the Abbot. The man of the cloth rose from his seat and set off slowly and solemnly around the long table. Those that remained bowed their heads as the Abbot moved to stand before the handmaiden. He offered her his blessings. Speaking in Latin and with his broad back to the table shielding his actions, he traced the sign of a cross before her body, passing the edge of his flattened palm firstly in a line directly down between her breasts, then secondly in a crosswise direction, and in doing so, brushing lightly but deliberately against the tips of her nipples.

Gwyneth spoke quietly to the Abbot. ‘Holy Father I am innocent of all crimes, please tell them I am innocent,’ she whispered. ‘I beg of you Holy Father, tell them I am innocent.’

The Abbot placed a hand upon a breast to cover her heart. ‘Then you have nothing to fear my child,’ he replied. ‘God will be your witness and your strength.’

The handmaiden tried to move away but her chains hindered her movement and the hand followed. ‘Then pray for me Holy Father. Please pray for me,’ she begged.

The Abbot chanted another little prayer and shuffled even closer. Once more he traced the sign of the cross before her breasts, but on this occasion with the edge of his hand remaining in contact with her body on both the downward stroke between her cleavage and on the lateral movement across her breasts.

He concluded in Anglo-Saxon with the words; ‘Put all your trust in God my child. May he remain with you, and protect you from evil, forever and ever. Amen.’

The Baron waited patiently for the Abbot to conclude his blessing and return to his chair before speaking. ‘Amen,’ he repeated loudly as the Abbot sat down.

He then addressed those seated at the table. ‘Since the accused does not readily admit to her guilt, then gentlemen we must work hard for that confession,’ he told them.

After a brief pause the Baron turned to the accused. ‘Gwyneth Fletcher, you have now denied this court on two separate occasions, and our patience grows thin,’ he warned her. ‘Under the laws of Lodelowe, and of the Council of the Marches, deny this court a third time and we will have no option but to resort to other, more brutal ways of extracting the truth from your lips. Do you understand what I am saying?’

Gwyneth understood only too clearly. This was no idle threat from the Baron. Having lived and worked within the walls of a castle for the past five years, she was fully aware of the threat and danger that lay coded within the Baron’s words. By the kitchen fires at night she had been told many a gruesome tale of what went on down in the castle’s dungeon, and had seen with her own eyes the crippled wrecks of bodies forced to hobble and crawl their way to the gallows. She closed her eyes and said a little prayer before nodding her head in response.

But a nod was not good enough. ‘Speak up wench so that your response can be recorded accordingly,’ stated the Baron. ‘Tell this court you understand.’

The handmaiden swallowed a dry mouth. ‘Yes Sire, I understand,’ she replied.

The Baron motioned for the shoe that contained the ring to be passed along the line. Bardolph being seated at the far end of the table passed it along. On receiving the shoe, the Baron held it high for Gwyneth to see.

‘Wench, is this your shoe?’ he demanded.

Gwyneth stared blankly at the shoe but give no reply.

‘Answer me wench so that it may be recorded,’ snapped the Baron and sounding more impatient than ever.

Gwyneth nodded her head, but remained unsure of how to answer. For this was not her shoe. It belonged to the Lady Adela.

‘Sire, the shoe was given me by Lady Adela so that I may have something to wear on the journey south,’ she replied and trying to put things into their proper context.

The Baron scowled. Not getting the answer he desired he rephrased the question. ‘Gwyneth Fletcher, I demand a straight answer. Were you wearing this shoe at the time of your arrest at the ford? Just answer this court, yes or no?’ he said.

With the question rephrased Gwyneth had little option but to reply honestly. ‘Yes Sire, it is the shoe I was wearing at the ford,’ she admitted quietly.

Satisfied, the Baron continued. ‘And is this the same shoe you wore in the cell when searched?’

Even more quietly and with head bowed she whispered her response. ‘Yes Sire, it is,’ she said.

The Baron waited for the Scribe to take everything down. Keeping the shoe held high, he raised the flap in the heel and removed the signet ring wrapped in parchment. He placed the shoe upon the table, unwrapped the ring and held it aloft.

‘So if you do not deny this shoe is yours, then pray explain to this court how this ring came to be found inside?’ he demanded, with a hint of incredulity to his voice.

Gwyneth shook her head and answered back in a raised voice that held a touch of contempt for what was being implied. ‘Sire, you are wrong,’ she answered. ‘I swear before God that I know nothing of the ring.’

The Baron thumped the table and tried to contain his temper. The handmaiden not only blasphemed and took the name of the Lord thy God in vain, but also issued an insult to his person. As upholder of the law, no one had the right to accuse him of being wrong.

‘What!’ he exclaimed, shocked by the tone in which she had addressed his court. ‘With all this damning evidence, you have the audacity to say that I am wrong? I must warn you, we who sit in judgement are no fools and not to be trifled with.’

Gwyneth looked firstly to the Baron and then to all the other faces seated at the table. She pulled herself together and answered even more loudly and clearly so that all those assembled would understand the message she was trying to get across. ‘Sire, and my noble lords,’ she said, ‘on my solemn oath I do swear before you and before God that I know nothing of the ring found within my shoe.’

The Abbot audibly tutted and began to shake his head. ‘Sire, this wench continues to take the name of the Lord thy God in vain,’ he said. ‘This amount of blasphemy cannot be allowed to go unpunished.’

The Baron held up a hand to silence the Abbot. For a while he stood rocking backwards and forwards in his chair, for anger raged within him also. The handmaiden had raised her voice and shown nothing but contempt for his court. Eventually he calmed down enough to speak. ‘Me thinks gentlemen, this wench has uttered her third and final denial and the time has come for us to put a stop to this nonsense. Is this not the verdict of you all?’

Captain Osbald took no time in replying. ‘Aye my Liege, you are right as ever,’ he said. ‘This court cannot remain lenient with her a moment longer. It is like you say, the time for nonsense is over. Let her taste the hot irons, and let us get some truth from her lips.’

Squire Henry Stokes was similarly quick to voice his opinion. ‘I see no other course of action left open to us my Liege,’ he said. ‘The wench procrastinates. She has denied this court on three separate occasions, and the situation can no longer be tolerated. I agree with the good Captain, her tongue must be loosened. Let the irons do their work.’

Next was the turn of the young Edwin de Mortimer. All eyes turned his way.

‘I can only agree with Squire Henry and the Captain my Liege,’ he said. ‘This court must take what steps are necessary to ensure that justice is done. We are left with no other option.’

One side of the table had now passed its verdict and all eyes turned towards the Abbot and Bardolph sat to the right of the Baron and beyond the scribe. It was the Abbot that spoke next. He sat in prayer, his podgy hands together before his face. He lowered them to the table before speaking. ‘I must agree with everything that has been said my Liege. Three denials and three impious lies have issued from this young maiden’s lips: One so blasphemous that it cannot be allowed to go unpunished. Lucifer is within her. The irons must be used, and made to burn deeply so as to reach the soul, and salt must be applied liberally so as to expunge the devil from her loins.’

The Baron nodded his head. He was in total agreement with the Abbot’s sentiments. However, he could progress no further until receiving one last verdict. He waited patiently for the man seated at the end of the table to give his response. But when it was not readily forthcoming he spoke along the table.

‘Bardolph, good Sire, this court needs to record a statement from all those that sit in judgement,’ he said.

Bardolph stared back long and hard, and then to the handmaiden, now sobbing gently. A lock of hair was cast down over one eye, and wet dishevelled strands clung to the side of her face. He wished that it was within his power to save her from further torment, but already the verdict was four to none, and he was well aware that nothing he could add would alter the final outcome. The handmaiden’s fate was already decided and the Baron’s justice would run its full and brutal course. In the end he prayed that she should break quickly, for there was nothing in his power to save her.

Bardolph spoke his thoughts, apologising for his reticence. ‘Pray forgive me my Liege for not giving an immediate answer,’ he said, ‘for I remain ignorant of the laws of Lodelowe and of the Marches. My knowledge is only of Wessex and the laws that prevail at the King’s court at Winchester. But if the law requires three denials before sentence of persuasion be passed, then I can confirm I have heard this young maiden deny the charges laid out before her on no less than three separate occasions. You may mark my words on that, for that which remains a fact cannot be denied. But as for what is to follow, then I am neither for nor against the applications of the irons. For it is my belief that this court will glean very little from her, save that she remains loyal to her mistress, and that her soul holds nothing more than youthful naivety.’

Murmuring from the crowd filled the hall, and the Abbot seated next to Bardolph glared silently back at him. Bardolph could see that his words had not found favour in certain quarters. However the Baron was more conciliatory, recognising that if to succeed, then this trial needed the full blessing of the King’s Falconer.

‘Fine words and well spoken Sire,’ uttered the Baron and breaking the silence, ‘and I must echo your sentiments, for it is clear this wench says what she does in order to protect others, and as yet cannot foresee what dire consequences this action holds for her. However I must remind you that it remains the duty of this court to establish the truth in this matter, and we must apply the full force of the law with unrelenting pressure until those ends are met. So do you not agree that the irons offer the only means left to seek the truth?’

Bardolph regretted that it should come to this. However this was not his home and not his problem. The road south beckoned and with autumn approaching he had much to do in the training of his young fledglings. He nodded his head.

‘I remain guided by your judgement in such matters my Liege,’ he said sadly. ‘If the only way left open to this court in seeking the truth is by means of hot irons, then so be it. I offer no objections.’

The Baron waited for the Scribe to stop writing before turning to the handmaiden. Tears trickled down her cheeks. She had listened to their verdicts and could find not one ally amongst them. Every one of them thought her guilty. In desperation she made one last plea for mercy.

‘Please, I beg of you, do not do this to me,’ she called. ‘I am innocent of all crimes. Pray do me no harm.’

Affronted by the outburst, the Baron called upon Sergeant Cuthred who was stood one pace behind. ‘Sergeant, silence this wench,’ he said. ‘She remains as impudent as ever. In future she must only be allowed to speak when this court requests her to do so.’

Sergeant Cuthred stepped to the front. Turning to face Gwyneth he removed a gauntlet and raised a hand as if to strike. On seeing the threat she shut her eyes and turned her head away. The strike however did not materialise and the Sergeant lowered his hand, but all the same she remained with her head to one side whilst she listened to the Baron pronounce sentence upon her.

The Baron placed his hands together and spoke. ‘Gwyneth, daughter of Thomas the Fletcher of Salopsbury,’ he said, ‘this court has in accordance with the laws of Lodelowe and under the jurisdiction of the Council of the Marches, allowed you ample opportunity in which to confess your crimes. You have been presented with the evidence and on three occasions this court has offered you the chance to openly and freely admit your guilt. But alas, you have failed to comply on every occasion and this court simply cannot continue in this vain. There comes a limit to our generosity and a time when the truth must be out. That time for you, alas, has now come. We tire of your stubbornness, and you therefore leave us with no alternative. This court decrees that your tongue be loosened by whatever means we deem fit, and so, Gwyneth, daughter of Thomas the Fletcher of Salopsbury, this court commits your body to the hot irons. So help you God!’

‘Amen!’ voiced the Abbot on hearing the Baron’s stern words.

‘Amen,’ added the young Edwin de Mortimer and Squire Henry Stokes in unison.

All eyes next turned to the little man stood in the great fireplace. Sparks flew as he thrust and turned a row of irons deep into the glowing embers of the brazier.

Barik signalled with a shake to the head that he was not ready. The coals were not to his liking and more pumping of the bellows needed to encourage the flames. The chimney in the hall was not ideal for heating irons.

The Baron acknowledged Barik’s signal with a nod to the head. He turned to address his distinguished guests. ‘Gentlemen, it seems we have a slight delay,’ he told them. ‘Come let us partake of a goblet of wine whilst we wait. I have some goodly Norman wine from the vineyards of Anjou.’

The Baron snapped a finger and a young boy appeared. He carried a silver tray, a flagon of wine and seven silver goblets. He poured the wine into the goblets.

When all goblets were filled the Baron spoke to his guests. ‘Gentlemen pray do quench your thirst,’ he said. ‘We have a long day before us and are in need of much sustenance.’

The Abbot was first to the tray. He blessed the wine and took a goblet. The others rose and moved to collect theirs in turn.

Bardolph was last to rise. Taking up the last goblet he moved to stand beside the Baron. ‘Pray tell me my Liege,’ he said, ‘surely one ring and one necklace do not constitute a great deal towards the recovery of all that was taken from your strongroom? Pray tell me, just what was taken? Not as a list but in physical size?’

The Baron pondered upon Bardolph’s question, but clearly had no answer. He had seen an inventory of the missing items, but had never visualised the actual size of the haul.

‘In sacks maybe? One sack? Two sacks? Several sacks?’ suggested Bardolph and trying to be helpful.

Captain Osbald, standing alongside and overhearing the conversation, came to the Baron’s aid. ‘At least three sacks my Liege, maybe four,’ he interrupted. ‘The robbers must have taken at least three, possibly four sacks of treasure, for there were silver plates and goblets in the haul as well as many gold coins.’

Bardolph pondered for a while before speaking. ‘Ah!’ he exclaimed. ‘So this begs a second question. If one necklace and one ring are all that have been recovered then where is the rest?’

The Baron held out a hand towards the Scribe who was stood some distance away. ‘Hand me the map Scribe,’ he called.

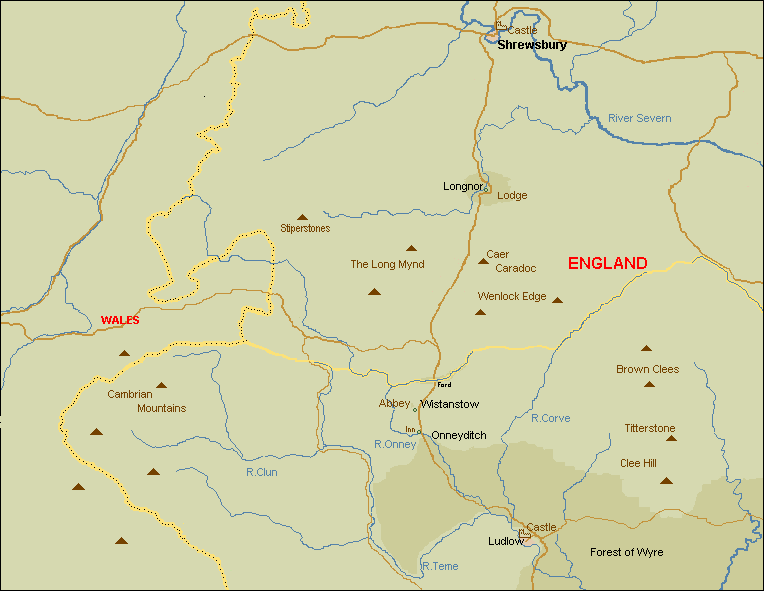

The Scribe collected a scroll from alongside his escritoire and passed it down the table. The Baron spread the map out upon the surface and held the corners down with the tray and the wine jug. It was a map of West Mercia and of the Marches, and included the town of Lodelowe and the city of Salopsbury.

‘Pray look here,’ said the Baron and indicating with one finger the various points on the map, ‘to the north lies Salopia, and here to the centre lies Salopsbury and the castle of the Fitzgeralds. Whilst down here to the bottom is Lodelowe. This is where we are now,’ he said and tapping a finger on the spot. ‘Reportedly Lady Adela’s party was travelling to the Cinque Ports to board a boat for France. The ports are down here, to the south and east and off the map. This line here, this is the road they should have been taking. This is Watling Street, an old Roman road that leads to London and the Cinque Ports, and as you can see this road does not pass through Lodelowe. But all the same they chose a different route. I therefore beg the question? Why go out of their way when it is not necessary? Could it be that my treasure is buried somewhere in my forest, and their intention was to collect it on their way? I think this to be the reason, does’t you not agree?’

Bardolph rubbed his chin thoughtfully and studied the map. In time he replied. ‘Your reasoning is sound and logical my Liege. I find no fault,’ he agreed.

The Baron placed a hand upon Bardolph’s shoulder. ‘If my treasure is buried somewhere in my forest and this wench knows of its whereabouts, then I will have it from her lips. I swear before God that this will be so,’ he said with a hint of bitterness to his voice.

As the Baron spoke there came a shout from alongside the fire. ‘I am ready my Liege,’ called Barik. ‘The irons are heated.’

The Baron looked to those assembled about the table. ‘Pray gentlemen, retake your seats,’ he told them. ‘My court is back in session.’

Stood to the centre of the hall the handmaiden could only ponder upon her fate. She shook with fear. As the Abbot took his seat she called out to him. ‘Holy Father, pray give me your blessing,’ she called.

The Abbot, on hearing, turned to the Baron. He had not expected this intervention and looked a little surprised.

The Baron raised a finger and pointed to the handmaiden. ‘You may proceed,’ he told the Abbot. ‘The accused may receive a final blessing before our work begins.’

The Abbot rose awkwardly and walked around the long table. As he approached the handmaiden he recited a verse in Latin. ‘Qui nos rodunt confundantur et cum iustis non scribantur,’ he chanted.

Bardolph translated the words. The Abbot was saying; ‘May those who slander us be cursed and may their names not be written in the book of the righteous.’

Bardolph felt sorry for the handmaiden. She had asked for the Abbot’s blessing and these were not the words he should have spoken. Bardolph looked down the long table. There was no reaction from those seated, save that of the Scribe who was gently nodding his head. It was apparent to Bardolph that, other than himself and the Scribe, no one seated at the table had an understanding of Latin.

The Abbot came to stand before Gwyneth, his rather large and rotund figure shielding her from the table. With the edge of his hand in constant contact with her body, he traced the sign of the cross, firstly down between her breasts, then horizontally to brush across the tips of her nipples. Has he did so he chanted once more in Latin; ‘Pulchra tibi facies, capillorum series, a quam clara species.’

The Abbot’s words were low and whispered, but Bardolph with his keen sense of hearing heard every word. The Abbot had chanted; ‘Beautiful is your face, your braided hair; what a glorious creature!’

Bardolph seethed. The Abbot was taking gratification from her nakedness and this was no way for a man of the cloth to behave. Bardolph’s instinct was to protect Gwyneth. She needed someone to stand up for her. He was aware however that this trail was just a charade, a face-saver for the Baron, and everyone concerned were just pawns in his game. Inwardly he wanted to speak out and defend the handmaiden, but his loyalty to the King overrode such action. His priority lay with his peregrines, and he realised this court would pronounce its verdict regardless of anything he said or did. He took comfort from the fact that this trial would be soon over and he would be on his way.

As the Abbot returned to his chair, the Baron with voice raised so that all those assembled in the hall could hear, called to Barik stood in the fireplace. ‘Jailer, you may proceed. Do your work,’ he said.

Barik slid his hands into a thick pair of leather gauntlets and took hold of the protruding end of an iron bar buried deep in the coals. With a stirring motion he re-kindled the embers. Immediately sparks flew, illuminating the hall and casting moving shadows against the grey granite walls. Slowly he withdrew the glowing brand and set off for the centre of the hall. He arrived to take up position immediately behind the handmaiden. In his hands he grasped a brand of wrought iron, the end of which glowed brightly in the shape of the rampant lion of Lodelowe.

Gwyneth tensed her body. With the arrival of the brand came the prickly sensation of a fierce heat radiating down the back of her spine. Instinctively she swung around to investigate, but Sergeant Cuthred knocked her back.

‘Face the court,’ he told her sternly.

Gwyneth turned to face the table and began to recite a small prayer, asking God to give her strength and the will to survive.

The Baron waited for Gwyneth to conclude her prayers. He then spoke loudly so that everyone in the hall should hear. ‘Gwyneth Fletcher,’ he began; ‘are you now ready to confess your guilt? This is your last opportunity to speak openly before the hot iron strikes. Even at this late hour this court is willing to withdraw the irons. So we ask you for one last time: Are you prepared to relent your stubborn ways, and confess to this court the true nature of your crimes?’

Through clenched teeth Gwyneth gave her reply. ‘My Liege,’ she told the Baron, ‘I am innocent. I know nothing of the ring. I can tell you no more. Please, I beg of you, do not do this to me.’

The Baron tutted loudly and shook his head from side to side. ‘You can tell this court no more because you do not choose to tell us. Is this not the truth?’ he snapped angrily.

Gwyneth shook her head and tried to justify her words. ‘No my Liege,’ she said, ‘I swear to you all, I know nothing of the ring, and this is the solemn truth. I swear this before God.’

The Abbot protested immediately, for once more this wench did blaspheme in the name of the Lord thy God. But the Baron was quick to hold up a hand and silence him. He placed his hands thoughtfully together as if in prayer. After a long pause he spoke through his hands.

‘Jailer,’ he said, ‘this court can no longer hold back its leniency. Proceed with the irons.’

Taking his cue, Barik moved to the front. At the same time Sergeant Cuthred, from behind, took a firm grip of Gwyneth’s arms. She struggled to break free as the brand became raised. The heat was unbearable even at a distance and she screamed. Barik moved to thrust the glowing iron against her upper abdomen, a point on Gwyneth’s body just above the chains that connected her wrists. He was about to strike when halted by a cry from the table.

‘Wait jailer. Draw back the irons,’ there came a call. All eyes turned to Bardolph. He rose and addressed the Baron.

‘My Liege may I be permitted to put one last question to the handmaiden before the irons are applied?’ he enquired.

The Baron clasped his hands before his face and considered the request. After much deliberation he replied. ‘Pray tell me good Sire, what question needs to be put to the wench at this late hour?’

Bardolph remaining standing addressed all those seated at the table. ‘Gentlemen, this court demands answers as to why the Baron’s ring was found within the heel of the handmaiden’s shoe,’ he reasoned. ‘I agree she must surely be hiding the truth. But as yet I have not heard the reason asked why the Lady Adela and her party should venture this way. Of this I am most curious.’ Then addressing the Baron directly he added; ‘My Liege, did you not speak earlier saying that the road the party was taking not to be the direct route between Salopsbury and the Cinque Ports? Surely this court demands an explanation as to why this should be so?’

The Baron nodded in agreement. He too was curious but held his own theories on the matter. He was convinced his treasure to be buried somewhere within the Forest of Wyre, and that it was the intention of these people to collect it on their way through. However he was also very much aware of his ultimate objective. For his plan to succeed, then a verdict of guilt upon the handmaiden needed the full blessing of this court, and this included Bardolph.

‘You may proceed,’ he told him. ‘You may put your question to the accused.’

Bardolph beckoned Barik to step away. Then with the threat of the hot iron gone, he addressed the handmaiden. For comfort he spoke her name, saying; ‘Gwyneth, pray tell this court why you did’st so come this way? And tell us this, why did’st you and your party find it necessary to venture south to Lodelowe when the Cinque Ports are to the south and east?’

Gwyneth swallowed deeply and considered the question. Slowly and hesitantly she began to relate what little she knew. It probably had nothing to do with ring found within her shoe, but it did explain her party’s detour to Lodelowe.

‘Good Sire,’ she explained, ‘on the night before our departure from Salopsbury I spoke with the Lady Adela and she enquired of my parents. I told her that my father was dead and my mother no longer resided at Salopsbury, and that she does’t now live somewhere within the walls of Lodelowe. Lady Adela was most kind to me, and promised that I should see my mother on our way to the Cinque Ports, since the detour was small and would add very little to our journey. We were to spend our first night with the company of the Abbess at Wistanstow, then travel to Lodelowe the following day. But we never reached the abbey. We were waylaid at the ford and there our escorts were slain. Good Sire, I know nothing more. Please believe me. I know nothing more.’

With the mention of the abbey all eyes turned to the Abbot. All those seated were waiting for confirmation. The Abbot shrugged his shoulders before speaking. ‘I know nothing of the affairs of the Abbess,’ he told the court. ‘However she is a Fitzgerald. She is the brother of Herbert, the new Earl of Salopsbury, so some arrangement for stay may have been made.’

Bardolph stroked his beard thoughtfully. Gwyneth’s tale was all very well, but the Baron and his court needed a whole lot more if he was to save her from the hot irons. Her tale still did not account for the ring in her shoe. He raised the question of her mother, saying; ‘Your mother, what is her name?’

Gwyneth was quick to reply. ‘Madeline,’ she answered. ‘My mother’s name is Madeline.’

The Baron raised a hand to interrupt Bardolph and put a hold on any further questioning. Having heard what Gwyneth had to say he was curious as to the identity and whereabouts of her mother. He turned to Captain Osbald seated at the far end of the table. ‘Captain, do you know of this woman?’ he asked. ‘This Madeline the wench speaks of?’

Captain Osbald nodded his head. ‘I believe so my Liege,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘If I am not mistaken she is a whore at the local tavern.’

The Baron put his hands together in thought. He was now seeing things in a very different light. He was aware that several whores operated from the tavern within the town, and also knew of the relationship they formed with many of his men. He could therefore foresee a possible link between Gwyneth’s mother and the robbery. He reasoned that if anyone needed inside information, then what better way was there than to get it from the comfort of a bed?

Slowly a picture began to form and the Baron spoke his thoughts aloud. ‘This woman?’ he queried. ‘This Madeline the accused speaks of? She would have no doubt slept with many of my men? And if this were to be true, then would it not be easy for such a person to obtain intimate knowledge of my strong room, and my security, and the watch, and the changing of the guard? And this information in the hands of someone with a mind to robbery could prove most invaluable, could it not? Does’t I not speak the truth?’

Captain Osbald agreed most heartily with the Baron. ‘It could very well indeed my Liege,’ he replied. ‘This wench may well be telling us the truth when she speaks of this Madeline. This whore is very popular with my men, and could well have been responsible for the passing of information.’

All those seated listened with interest. There came mutterings from the Abbot, Squire Henry Stokes and the young Edwin de Mortimer. It seemed they too were very much in accord with the Baron’s thoughts.

Turning to confront the handmaiden, the Baron addressed her in a loud and authoritarian voice. ‘Tell this court more wench,’ he said. ‘Tell us more about your mother. Was she involved in this conspiracy too? Tell us! And tell us whom it was that did the robbery? Could it possibly have been the soldiers that escorted you? Was it they who raided my strongroom? And was it they who distributed my stolen jewels, perhaps my ring to you, my necklace to the Lady Adela, or even as a favour for your loyalty, or more likely as a reward for your involvement? Is this not the truth? You were given the ring, and Lady Adela the necklace, as a reward for your silence? You are just as much as guilty of this crime as they, are you not? Now confess. Admit to this court your obvious guilt.’

The handmaiden turned pale and fraught. The Baron had put so many questions and she could think of no reply. Nothing of which the Baron spoke was true. She froze and closed her eyes. She could no longer think. Her mind had gone blank. All she wanted to do was curl up and die.

‘Answer me wench!’ bellowed the Baron. ‘It is true isn’t it? You knew that the ring was stolen? Stolen by the men that brought you here! So you concealed it within your shoe? Confess wench, confess and put an end this ridiculous charade.’

Gwyneth remained confused and did not reply. She was thinking perhaps there was some truth to the Baron’s words. Perhaps this is how the ring did get into her shoe. Perhaps the soldiers that escorted her party did commit the crime. Perhaps they gave the necklace to the Lady Adela and it was she that concealed the ring within her shoe. But with all this said, to implicate her was a lie, a total and utter fabrication of the truth. She was innocent. So why did they not believe her?

Impatient for an answer the Baron called to Barik, saying; ‘Jailer, do your work. Bestow upon this wench the pain that does’t accompany such blind stubbornness.’

The handmaiden gave a sideways glance and caught sight of the little man stepping forward with a glowing iron in his hands. She closed her eyes and began to pray.

‘Confess wench!’ yelled the Baron from behind the table.

Barik moved to stand before the handmaiden. Sergeant Cuthred gripped her arms from behind. She struggled to break free but the Sergeant’s hands remained firm. Even though the brand had not yet struck she could feel the heat burning against her body. Suddenly she snapped. With a quivering bottom lip she called for mercy.

‘Stop! Please stop! I confess,’ she cried. ‘I confess. I confess to everything. Lady Adela put the ring in my shoe, and the men that accompanied us did the robbery. Just don’t let him hurt me! Please, please don’t let him hurt me!’

Sergeant Cuthred released the handmaiden’s arms and she dropped to her knees. Here she remained, her body shaking and heaving with sobs.

The Baron slumped back on his chair. With hands placed before him as if in prayer he gave orders to his Scribe. ‘Scribe, prepare a fresh confession,’ he said.

On hearing the Baron’s words the Scribe sorted out a brand new scroll. He had a fresh confession to write, one that included the three soldiers that escorted Lady Adela’s party, and also included a mention of the whore Madeline.

Turning to his Sergeant the Baron issued further orders. ‘Sergeant, arrest this Madeline and take her to my dungeon,’ he told him. ‘Then conduct a thorough search of the tavern in the town. Look for anything that may have come from my strongroom. Leave nothing upturned. Ransack the place if necessary, strip it of its floorboards if need be. But be sure to leave nothing upturned. Is this clear? If my treasure is hidden in the forest, then this Madeline will be sure to know of its whereabouts.’

Finally, the Baron addressed all those seated at the table. ‘Gentlemen at last we have it!’ he pronounced. ‘Not only does’t we have the confession we does’t so desire, but me thinks we have found someone who knows the secret to my treasure’s whereabouts.’

On conclusion the Abbot chanted a few words in Latin, and both Edwin de Mortimer and Squire Henry Stokes clapped a small ripple of applause. After a short silence the Baron spoke again.

‘Gentlemen, you have all done my court proud this day,’ he told everyone. ‘May I congratulate you all on the fine work done? Now I suggest we partake of some much needed refreshment? Let us drink more of the goodly Norman wine that warms the heart. Then perhaps afterwards, once the accused hath made her mark, we shall return to the table and complete what we have started here today. Once again gentlemen, my hearty thanks to you all.’

Bardolph felt despondent at not being allowed to question the handmaiden further. He called to the Baron. ‘Pray tell me my Liege, what fate now awaits the handmaiden?’ he asked as chairs began to shuffle away from the table.

The Baron rose from his chair and turned to Bardolph. ‘She will be asked to make her mark upon her confession,’ he explained. ‘When this is done this court will reconvene and agree her guilt. Sentence will then be passed. As is tradition here at Lodelowe, on the day of the market she will be taken to the courtyard, tied by the wrists to the back of a cart and flogged through the streets to the gibbet where she will be hanged. No doubt there will be a goodly crowd present to partake in the spectacle. However we may make it a double hanging, with this whore from the tavern accompanying the handmaiden to the gallows. But we will see, there is no rush and justice will run its course.’

Bardolph felt sorry for the handmaiden but said no more. Slowly he followed the court from the hall to an adjoining room where wine and refreshment awaited them. Only the Scribe remained to conclude matters, and with the handmaiden down on her knees and sobbing deeply on the floor at the centre of the hall.

There was however one small item Bardolph carried with him. The scrap of parchment folded about the ring was now safely tucked away in his purse. He did not know why he had taken it. There seemed little point now that the handmaiden had confessed and pointed an accusing finger towards her mother. Yet somehow a doubt remained and this scrap of parchment he considered to be the only true clue into solving this mystery. His heart was telling him to remain at Lodelowe and seek out the truth. But his loyalties lay with the King of England, and this remained paramount. The peregrines in his charge simply had to be trained, and this had to be done whilst they were still young.

For the King’s Royal Falconer today was a very sad day indeed.

Chapter Eighteen

A banquet fit for a king awaited the Baron’s court. Those that stood in judgement, along with their servants and entourage, all were invited. The castle’s keep emptied slowly, each leaving in their own time and at their own pace; their destination being the Great Hall in the west wing of Lodelowe Castle. It was a day to saunter and enjoy the sunshine. Blue skies and a scattering of white fluffy clouds filled the air. The walk from the castle’s keep to the courtyard was pleasant, and because the path downhill, the exercise troubled no one, not even the Abbot who trundled slowly with the aid of a servant to each arm.

Whilst walking the steep and winding downhill path Bardolph found chance to speak to the Baron. It was not a conjured meeting, the two men coming side by side inadvertently, the Baron moving backwards through the rank in order to converse with the Abbot who brought up the rear. But this was a chance meeting Bardolph could not let pass and he took full advantage. As the two men’s stride brought them together, Bardolph slowed his pace to match that of the Baron.

With a courteous nod to the head, he asked; ‘My Liege, now that the trial of the handmaiden hath ended, I pray that I may be permitted to be on my way? For the King does’t eagerly await his birds and I must tarry in these parts no longer.’

The Baron stopped in his stride and placed a firm hand upon Bardolph’s shoulder. It had always been his intention to let Bardolph go once the trial was over. He had achieved all he wanted. The handmaiden had been found guilty and sentence passed, and the Royal Falconer’s signature upon the document was good enough to make the verdict look totally impartial.

‘Good Sire,’ he replied, ‘I hereby absolved you from partaking in anymore responsibilities regarding the affairs of Lodelowe. You are free to continue with your journey south. But I ask of you, pray do not leave my castle in haste, and pray do not depart until you have at least partaken in a little refreshment. For I have organised a goodly feast for this distinguished company. You in particular did’st serve my court well and I must thank you for all that thou did’st do and say. So please good sire, I beg of you, before you depart, allow me one last wish and dine with me. And besides, me thinks it would cast an ill-favoured shadow over Lodelowe should the good King Henry get word that I did’st not bestow a just and deserving reward upon one of his most trusted and faithful servants.’