My newest novel “The Girl with No Name” and its protagonist Danka Síluckt came into my thoughts at the beginning of October 2012. The plot unfolds in my fictional country of Danubia, but is different from my other novels because of its time-frame. The story spans a 10-year period in the middle of the 1700s, so none of my previously-created characters nor any trappings of 21st Century life show up in the newest project. The only character from a previous novel that briefly enters into "The Girl with No Name" is Maritza Ortskt-Dukovna, the wife of Prime Minister Vladim Dukov, who serves as the story's historian and narrator. I wanted write an adventure that examines an important era of Danubia's history, during which the country survived an external threat and began its transition from a post-medieval society into the modern country that appears as the setting of my previous novels.

In "The Girl with No Name" I seek to explore, both for myself and for the fans of my previous Danubia novels, my imaginary country through the eyes and experiences of my character Danka Síluckt. I wanted to create a character that has the chance to observe all levels of Danubian society, changes as a result of her experiences, and matures as the novel progresses. She witnesses several events important to the history of the country and has a series of lovers and relationships as she travels. Through Danka’s travels I tried to lay out the Danubian Duchy’s geography, provide my vision of what the country actually looks like, and give names to its various cities, towns, and regions. Several people have expressed interest in using Danubia as a setting for their own fiction, so I wanted to give those readers a systematic lay-out of the country they can use as a framework for their writings. Throughout much of the novel her circumstances force her to be naked in public, in a society in which nudity is accepted and sometimes mandated.

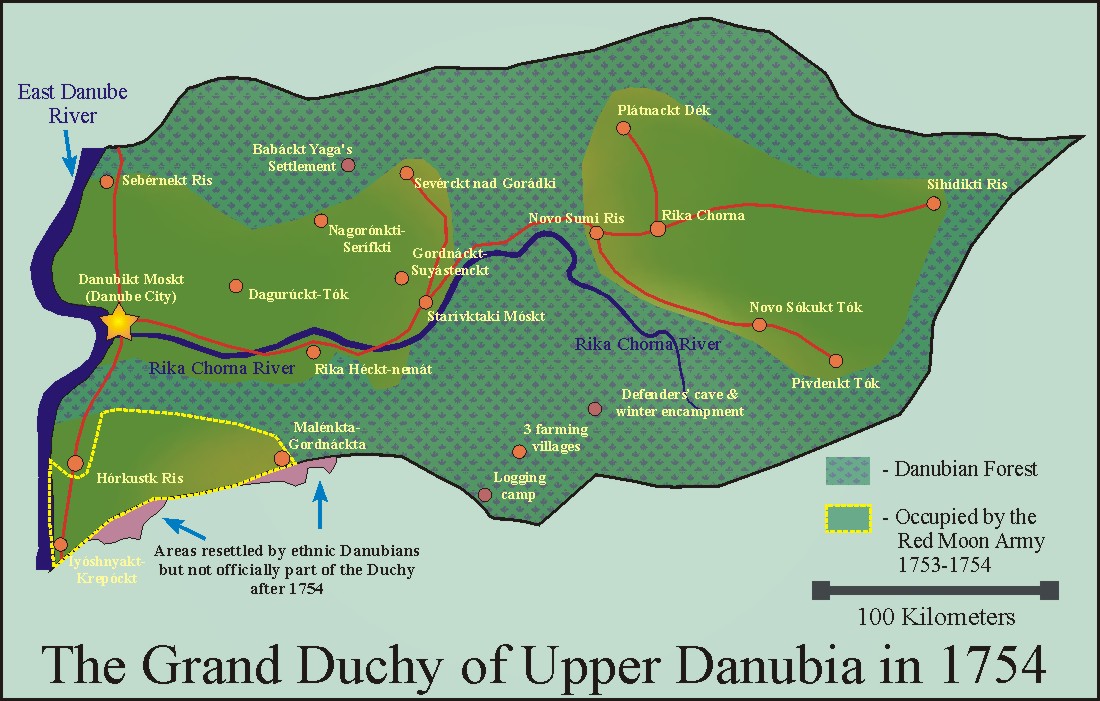

In my previous novels I have been purposely vague about the countries surrounding Danubia’s borders. Because of the way I wrote this particular story, I was forced to be a bit more specific, but still sought to avoid writing anything that conflicts with real-life European history and geography too blatantly. For the purposes of "The Girl with No Name" I had to create a second imaginary nation (the Kingdom of the Moon) that invaded the Duchy during 1754, but once again, tried to minimize having to alter real history from that time-period. The Kingdom of the Moon is a fictional entity that existed during the mid-1700’s and then disappeared in 1764, just long enough to meet the needs of my story’s plot. To be more specific about Danubia’s location, territory occupied by the Ottoman Empire lies to the south, Austria and Poland lie to the north, and Russia lies to the east. If Danubia existed in real life, it would be somewhere close to the region of Transylvania.

The plot takes place during the European Enlightenment, a time in which Danubia was transformed from a semi-medieval country into a modern one, largely due to the decisions of my character the Grand Duke. Some details of the Grand Duke’s behavior and goals are modeled after real European leaders at the time, most notably Catherine the Great of Russia and Fredrick the Great of Prussia. The Grand Duke's rival, the Vice-Duke of Rika Chorna, is loosely based on the royalty of France in the early 1700s for fashion, and the royalty of Spain for incompetence, which at that time was in decline due to extremely weak leadership.

Another difference in the creation of this novel was how I wrote it. In all of my previous novels I wrote the story from beginning to end. While writing "The Girl with No Name" I started writing the first chapter and the last chapter simultaneously. I wrote the chapters featuring Danka's time with the Grand Duke and the battle scenes next, and finished by filling in other events that take place in the middle of the novel. This was the first time I wrote the beginning and the conclusion of a novel together, before writing anything else. There have been previous projects in which I started writing without even knowing how the story would conclude, but in the case of Danka Síluckt’s adventures, I knew from the beginning how she would end up and how her adventure would finish.

Introduction - By Master-Historian Maritza Ortskt-Dukovna

Every country has its legends; the stories of people whose lives have transcended historical reality into that strange space between truth and fantasy. The Grand Duchy of Upper Danubia (or the Danubian Republic, as we prefer to call ourselves today) is certainly no exception to that common trend throughout humanity. In our case we have the stories of the Ancients, the Byzantine Priests who converted us, the exploits of King Vladik the Defender and his son-in-law, and songs about the Nymphs who defended the Duchy when almost all of its men had been killed.

However, Danubia’s favorite story has always been the saga of the girl-with-no-name. She shows up in historical records starting around 1750, and seems to have completely disappeared around ten years later. According to witnesses who claimed to have seen her, she was the prettiest, smartest, and nicest young woman imaginable. However, she was condemned to always be on the run, tormented by the Destroyer who followed closely behind her. In earlier versions of the story, the Destroyer, who at the time still was identified with the Christian Beelzebub, had a semi-human form and rode on her shoulder. Later, the story goes that she was running from the Destroyer. Because the Destroyer could never quite catch her, the Destroyer’s vengeance was inflicted on anyone the girl-with-no-name tried to love.

The girl-with-no-name’s adventures began at her home in Rika Heckt-nemat. The legend claims that she was so beautiful that the town’s other women couldn’t bear to look at her, and demanded that the council’s elders order her executed. The girl-with-no-name made a pact with the Destroyer to escape, and as soon as she was gone, the Destroyer condemned everyone in the town to die from the plague. The girl-with-no-name ran from province to province, trying to find love, protection, and peace. Many men loved her, and all of them died tragically. When the girl-with-no-name fled to Danúbikt Moskt and the Grand Duke fell in love with her, to punish the Duke, the Destroyer burnt the entire capital.

In the end, no one knew what became of the girl-with-no-name. For a decade she wreaked havoc on the people who crossed her path and then vanished without a trace. She became the favorite subject of campfire songs and a story to scare children, especially boys and teenagers. I think every mother in Danubia is guilty of telling her sons to avoid strange women who seem too beautiful to be true, especially ones in the woods or on the roads, because somewhere the girl-with-no-name continues her tormented voyage.

In 1855, on the 100th anniversary of the Great Fire that destroyed the nation’s capital, the famous Danubian poet and song-writer Dangúckt Tók compiled the stories of the girl-with-no-name into a song, which, although over-simplified, continues to be the best-known version of the legend.

The girl condemned to wander…

The anguish in her soul…

Her Path in Life is destruction…

The darkness rides her shoulder…

In her eyes there’s nothing but pain…

She will reach out to you…

Yes, you’re the one who’ll save her…

But take her hand…

…and her kiss will seal your fate…

The Destroyer holds out his bait… …and for you, oblivion awaits…

One important job of the historian is to attempt to reconstruct the events that inspired a legend. Many historians will reject a legend on impulse, only to later discover archeological or documentary evidence that does indeed offer proof that events described in the story actually did happen. I take a different approach, because I believe that most legends are embellished truth, not pure fantasy. Those stories exist for a reason: they were based on something that at one time was factual. Therefore, we must start our investigation by taking these ancient stories at face value and only dismiss details as we find direct evidence that discredits them. Even when events turn out to not have taken place as described by the chroniclers, we can use other research to reconstruct what actually did happen and often end up with a narrative that is considerably more interesting than the one given in a simplified campfire song.

The girl-with-no-name always fascinated me. As is true for many defiant Danubian children, I remember several times going out into the forest and looking for her, and receiving the switch for my efforts. As an adult, I pursued plenty of “serious” historical research endeavors, but in the back of my mind I always wanted to find the truth about the girl-with-no-name. Whenever I looked at church records and personal diaries for other projects, I always hoped to find some reference to her.

My search narrowed when I read the diaries of a city councilman written during the years immediately before plague struck down Rika Heckt-nemat’s population. One paragraph that fascinated me focused on the punishment of a peasant girl called Danka Siluckt in the early summer of 1750. He described her as unusually pretty for a peasant, mentioned that she worked for him, and added that she was sentenced to the pillory for stealing apples. She was then either expelled from the town and fled, or thrown into the Rika Chorna by the city guards to drown. The councilman complained that the mystery of the girl’s disappearance kept him up at night and troubled his conscience.

An account from the town priest for the same time period corroborated the councilman’s diary entry. The clergyman added that Danka Siluckt was viciously mistreated by the townsfolk, especially the women, while she was restrained on the pillory and that it was a shame to see such a pretty girl treated in such a harsh manner. Surely the Lord-Creator would punish the city for such an immoral act. Interestingly, the priest also seemed unsure whether Danka Siluckt drowned in the Rika Chorna or somehow managed to escape the city.

So…I pursued that lead, suspecting that the-girl-with-no-name had started out as the peasant Danka Siluckt. I followed clues around our country, establishing a time-line of her travels and the events of her life. The search was not easy, because Danka was forced to assume different names during her travels, but I am confident I accounted for the ten years of her wandering.

I took it for granted that she was in Danúbikt Móskt during the Great Fire of 1755, and found references to a woman who matched her description in the diaries of several of the Grand Duke’s advisors, castle song-writers, and concubines. The most important reference I found for that period of her life was in the memoirs of Alexándrekt Buláshckt, in which he described his escape from the Great Fire with his family and one of the Grand Duke’s mistresses.

So…years ago I started looking for the girl-with-no-name, and I found her. Danka Siluckt’s story inspired me more than I can put into words. She was not a tragic figure at all, but instead an incredible young woman who overcame tremendous odds in a Duchy that was much harsher than the comfortable country we live in today.

As I traced her footsteps, I felt I got to know Danka. She’s part of me, as she is part of everyone who is a citizen of Danubia. And…as best as I could reconstruct it, this is her story...

Chapter One – The Apple Thief

Danka Siluckt woke up before sunrise, as always. She carefully got out of her bed to avoid disturbing her younger sister, Katrínckta. She cast her sibling a resentful look, irritated that Katrínckta got to sleep in most days, a privilege she couldn’t ever remember having.

Danka stumbled around in the dark, trying to grope for her work outfit. The first item she located was her peasant’s vest, hanging from a wooden peg that had been wedged between two logs in the wall. She slipped the flimsy garment over her shoulders. The vest was not a top that would have been considered appropriate for a young woman in most European countries at that time: it was sleeveless and completely open in the front. It’s only function was to protect the wearer’s back from the sun: it was not designed for modesty or fashion.

Danka felt around the wall before placing her hand on the second part of her work outfit, a worn and very dirty brown skirt. She pulled the skirt up over her hips and tied the drawstring. The skirt, never an attractive piece of clothing to begin with, most definitely had seen better days. Threadbare, torn, and tattered, it was little more than a rag. It was in such poor condition that Danka thought about taking it off again and not bothering with it. If she were to just stay home and work around her parents’ homestead, she would not have worried about the skirt. However, on this day her duties would force her to leave home and work closer to town, so she figured it needed to stay on. The next item she put on was her work boots. The boots were the only part of her outfit that had any value at all: if nothing else, at least Danka’s father saw to it that all of his children’s feet were properly protected against their harsh living conditions.

Finally, she retrieved her mother’s hat. Danka would be working outside all day, so her mother had given her permission to use it. The hat was a typical peasant’s hat, with a broad brim designed to completely protect the wearer’s head and neck from the sun. Danka had heard that in other countries men and women wore different work hats, but in Danubia a peasant’s hat was a peasant’s hat. The sun in the fields was as harsh on women as it was on men, so there was no reason a woman’s hat should be any different from one worn by a man.

Danka cast another resentful glance at Katrínckta, as the younger girl stretched in her sleep and sighed with the satisfaction of the luxury of now having the bed to herself. Dishonored little brat…I ought to grab her hair, drag her out of bed, and make her come to work with me. But no…Danka didn’t dare do such a thing. She would dutifully go off and work, while Katrínckta would sleep in and then spend her day at the pond pretending to feed the family’s ducks, but in reality just soaking her feet in the water and staring at the flowers falling from the trees or the birds flying in the sky. Katrínckta was worthless, but if Danka dared lay a hand on her, their mother would immediately take the younger girl’s side and brutally punish Danka.

Oh yes…lovely Katrínckta …delicate Katrínckta …sweet Katrínckta …always Mother’s favorite. Danka quietly picked up her shovel. She resisted the urge to raise it over her head and slam it against her sister’s sleeping face. That would be nice…I wonder if she’d be so pretty after a hit to her teeth with this shovel…if she didn’t have her teeth, then they’d all think I’m the pretty one…

Danka struggled to open the rough heavy door that led outside. She decided to leave it open and let the daylight wake her family. It was just starting to become light, a clear early summer dawn that promised a hot day. The young peasant then unlatched the door to the chicken coop. As the fowl squawked and filed down the ramp, Danka walked behind the dilapidated structure to check on an important secret she was keeping from her parents.

Buried, in a broken cup, she kept a stash of copper coins. She had saved 15 coins so far…and hopefully by the end of the day she’d add a couple more to her collection. She knew that what she was doing was risky, but she needed a decent dress if she could hope to get married. If her parents ever could afford a dress, Danka knew that Katrínckta would be the daughter to receive it. Katrínckta would be the one to get married, while Danka would be expected to just keep working. No, that wasn’t going to happen. Danka would have her own dress, regardless of her parents’ wishes, and she would get married first. She grabbed a feed bucket before leaving for work. The feed bucket would be needed for her plan to get a couple more copper coins.

Danka emerged onto the muddy path that connected her family’s homestead to the outside world. She passed the duck pond her parents shared with another family of peasants; then passed several other dilapidated cottages. They were all the same: hovels made from stones and logs, hidden under trees and bushes, and surrounded by flocks of ducks and chickens. Some had vegetable gardens, but none of the properties was large enough to support a real farm. These were the dwellings of the lowest class in Danubian society…the day laborers.

Carrying her shovel and bucket, Danka followed a somewhat better road that was roughly paved with flat stones, passing larger properties. There were several orchards and wheat fields, all neatly kept and surrounded by fences or stone walls. The houses were attractive, and instead of duck sheds, rabbit hutches, or chicken coops, the farmers had built real barns.

Danka came up to an apple orchard and jumped the fence. She looked around for the best apple, which would be her breakfast. She was not worried about the orchard owner, because Danubian protocol allowed a poor person to take a single piece of fruit or a vegetable from a rich person’s property per day. The tradition was ancient, based on the Church teaching that the poor have the right to sustenance.

Danka hid the apple core under some leaves and took a second apple. Now, she did have to be concerned about the owner. She looked around before committing herself to the second piece of fruit, because protocol only allowed her to take one apple, not two. One apple was sustenance, but the second one was theft. Well, thought Danka…that’s just too bad. There will be more theft from this orchard when I come back…a lot more.

When she finished her second apple and had hidden its remains, Danka resumed her trek to work. She walked along a tree-lined road towards the provincial town of Rika Heckt-nemat. By Danubian standards the town was large, boasting a population of nearly 20,000 people. Only the capital, Danúbikt Móskt, and the eastern city of Rika Chorna were bigger. The city was built on a hill, with its medieval walls still standing, a relic of an age before cannons. On the south side of the town there was another irrelevant relic of the town’s past: a stone pier and row of docks that at one time serviced river barges, but now faced nothing but an open field. For centuries Rika Heckt-nemat had been a major river port, but four decades ago, when the Rika Chorna river flooded and changed its course to the north, the city was left landlocked. What had been a riverbed now was a series of swamps that were gradually being drained and converted to farmland. Hence the city’s new name: Rika Heckt-nemat, which translated to “the river doesn’t flow here anymore.”

* * *

Danka approached a group of workers whose task for the day would be to dismantle part of the now useless pier and move the stones to a site where the town council had decided to build a well. Most of Danka’s fellow workers were men. There were only a few women present, and of them, Danka was the youngest and by far the prettiest. She resented being expected to do such arduous work. I’m not a man, she thought bitterly: why should I be treated like one? However, she also knew that she would not be working as hard as most of the others, because undoubtedly, as soon as her male co-workers realized that she was still unmarried, they would vie with each other to give her small favors and even perform some of her duties. She smiled and flirted with a couple of the nicer-looking laborers, to encourage them to help make her day easier. Even though none of the men really interested her, Danka figured there was no reason she shouldn’t take advantage of her appearance while she still was pleasant to look at.

Wearing a ridiculous-looking tri-corner hat and an equally absurd felt coat, a city councilman approached the work site to explain the day’s tasking. Accompanying him was a servant lugging sacks full of hard-boiled eggs and small loaves of bread, which put the workers in a better mood. At least this man had the decency to pass out food before passing out orders.

As the workers sat and ate, the councilman explained what he wanted. The town was building a new well, cistern, and aqueduct; a project that would take advantage of the ample supply of stones and bricks from the remains of the old pier. The workers would be divided into a group responsible for tearing apart the pier, another to dig the holes needed for the cistern and well, and a third group that would move the materials needed for the new project. The councilman pointed at Danka, telling her that because she had brought a shovel, she would be part of the digging crew. A few minutes after finishing her egg and bread, she joined a group of 30 workers filing out to the planned well site.

Danka knew that no one in her group would be participating in actually building the new infrastructure. Their task simply was to get everything set up for the builders’ guild. According to the view of the townsfolk, the laborers were dishonored and uneducated rabble, good for nothing except tasks such as moving rocks and digging holes. Their Path in Life was to sit in their cottages among their chickens and ducks, and wait until they were needed for a project. Once the project was finished, they were expected to return to their cottages and stay out of everyone else’s way.

* * *

Danka spent the morning at the edge of an ever-deepening hole, glumly moving shovelfuls of dirt into a wheelbarrow. She did not have the hardest task of the group, but still, it was not a pleasant way to spend the day. The worst part of her job was knowing that her parents would not allow her to keep any of the money she was earning. It was her mother who had arranged for her to be here and who had negotiated her salary. Therefore, Danka’s parents knew exactly how much she was earning and would demand she surrender all of her pay upon returning home. After all, she was part of the household and Danubian tradition dictated that everyone in a household had to contribute to everyone else’s well-being.

While Danka may have burned with resentment that her younger sister was not with her at the work site, her parents did not see anything wrong with that. There would be enough money in the family to marry off one daughter, not two. If that daughter could be married to a husband who owned land; that would benefit everyone. So…the plan was to save Katrínckta for marriage and use Danka for working.

Danka didn’t say anything, but she had no intention of spending the rest of her youth working for her parents and watching them dote over Katrínckta. As soon as she could afford a proper dress, her plan was to leave home and move into town. She wasn’t sure what she would do next, but she had convinced herself that the only thing she needed to find a decent husband was to change what she was wearing. After-all, she remembered the legend of the servant girl who, with nothing more than some magic, managed to transform her work outfit into a bridal gown, and in doing so got the heir to the kingdom to marry her. Her expectations were not so lofty, but surely she could wander the city in her new dress and attract some handsome young guild member or city official. Why not? The girl in the story did it…

* * *

The pace of work slowed as the day got hotter. Shortly before noon, the city councilman returned to the work site, this time accompanied by a female city guard and a couple of wretched-looking criminals tasked with carrying the mid-day meal for the work crew. The woman looked about 30, was very tall, and was dressed in the long gray dress and white tunic used by all female guards in the Duchy. In her hand she held a leather switch. She had a haughty expression and carried herself with an air of severe elegance.

It was evident the two criminals were very afraid of her as they struggled with their heavy loads of food. Danka could see why as soon as they approached. Their bodies were covered with welts from their merciless mentor. After the food had been distributed they knelt, staring at the eating workers with gaunt faces. The guard turned to her miserable wards and Danka heard the following:

“You see, dishonored ones, how people who work get to eat. Look at that delicious food and think about how much you’d like to have some. Think about how that bread would taste in your mouth. Just think, if only you weren’t wearing a collar, how you too, could be sitting with these people and enjoying your meal. Think about it.”

The guard ended her statement with a savage blow to the back of each criminal, striking so hard that they cried out. Danka realized that the guard’s performance was not just to torment the criminals: it also was meant to scare the workers into staying out of trouble.

* * *

As soon as the guard and the criminals had departed, the workers passed around a jug of wine and lay under a tree to rest. There was no rush to finish the well, so they would take a nap and resume working when the sun wasn’t so strong. Danka did not join the others. She excused herself, picked up her bucket, and walked back to the orchard where she had eaten her morning apples. She casually strolled along the fence, checking to see if any of the orchard’s employees were in sight. Yes, unfortunately, a few women were picking fruit, but none close to the road. Danka decided to take the risk.

She set down the bucket and slipped under the fence. Crouching to stay out of sight, she snuck up to a tree and carefully pulled down an armload of apples. She quietly moved them to the fence; then returned to pick some more. As soon as she had taken about 30 apples and moved them to the edge of the property, she slipped back under the fence and carefully placed the fruit in her bucket. Trying to stay calm and maintain a neutral expression, she walked back towards the town. Instead of returning to her work site, however, she approached an inn just outside the south gate. She went around to the back where the kitchen was located, looking for a childhood acquaintance who now was working as a serving wench. Danka traded the apples for two copper coins. It was a fair deal with no questions asked. The serving wench needed cheap apples and Danka needed the money. Danka returned to digging site just as her work-mates were waking up. Perfect. Another two coins were safely in her possession.

* * *

Danka did not hurry home after she and the other workers were dismissed for the day. During her mid-day foray into the apple orchard she had noticed how many apples there were and that many of them were in perfect condition for picking. Surly the orchard owner’s employees would not have time to harvest them all. Surly another bucket-full of fruit would not be missed. Another chance to sell some fruit…and another chance add coins to her collection…

Why not?

The pedestrian traffic along the road was much heavier at dusk than it had been at noon, so Danka had to carefully time her entry into the orchard. It helped that a group of children had entered to help themselves to one apple each. Danka followed them and helped them pull down better pieces of fruit. As soon as the children finished and continued on their way, Danka crouched, waited for a few moments, then started grabbing apples and quietly placed them in her bucket.

In spite of her caution, she was being watched. Farmer Tuko Orsktackt crouched only a few fathoms away, drawing upon his former career in the Grand Duke’s forest archery battalion to observe the thief without being detected. Danka blissfully shook the branches and continued to pluck fruit as the property owner noted, in careful detail, what she was doing. Farmer Orsktackt was a meticulous man, and wanted to make sure his legal complaint against the thief was completely accurate.

Danka moved back to the fence with her bucket full of apples. Instead of heading home, she returned to the inn and exchanged her loot for another two coins. Four coins in one day…an excellent take for such an impoverished girl. And to think…tomorrow she’d get another four coins. She’d have her dress bought within just a few weeks at the rate she was going.

Farmer Orsktackt quietly followed her to the Inn, and observed enough to make sure he was correct in his assumption the girl was selling the fruit instead of taking it to her family. Excellent. There would be no appeal for clemency, no sad stories about starving children or sick parents. As soon as Danka left, Farmer Orsktackt entered the inn and bought a beer and one of his own apples. Yes, indeed, this apple came from his orchard. He now had everything he needed to send the pretty young thief to the pillory.

* * *

Danka returned to her parents’ house to spend what would be her final normal night with her family. As always, nothing but unpleasantness awaited her. Her parents greeted her by demanding to know why she had returned home after dark. Not satisfied at Danka’s claim that she had tried to take a shortcut and ending up getting lost, Danka’s father struck her across the face and accused her of having a lover.

A lover…oh…if only that were true…if only...and it will be, soon enough. I’ll show you…all of you…when I’m in the city with my fine dress and I get married and have my nice house…I’ll see to it that Katrínckta wears a collar and spends her entire life shoveling pig shit…and I’ll make you watch. I’ll show all of you…

Dinnertime came and went. Danka’s father sat in the only chair the family owned, while Danka, Katrínckta, and two younger brothers sat on the floor. They ate out of a pot with a large spoon they had to take turns sharing. It was a wretched existence, but it was the only one the Siluckt children had ever known.

Later that night, when she closed the chicken coop, Danka added four coins to the broken cup and covered it back up. Then she took off her clothes and got in bed with her sister, the person she most hated in the world.

* * *

Early the next morning, Farmer Orsktackt stationed two of his employees within sight of the fence and instructed them to report to him immediately as soon as they saw a very pretty, but very poorly dressed, young peasant woman carrying a shovel and a bucket enter the property. Sure enough, shortly before sunrise Danka showed up, ate her allotted apple, and then took off for work. Curious to see where she was going, Farmer Orsktackt followed her towards the town.

Hmm…interesting…so it turned out she was an employee of the city council, working on that new irrigation system. More evidence to damn her at trial, given that Farmer Orsktackt was one of the project’s most important financial contributors. On top of everything else, the orchard owner was a personal friend of the city councilman in charge of the work crews.

Farmer Orsktackt decided to pay a visit to his friend instead of dealing with the hassle of going into town and trying to get an appointment with a court official. Each saluted the other by thumping his right fist against his left shoulder. After exchanging greetings and getting an update on the progress of the digging, the farmer inquired about the girl with the bucket.

“You mean the pretty one? Yes, her mother was the one who set her up with this job. I assigned her at the pit to shovel dirt into the wheelbarrows. Not the best worker, but the men like looking at her, so she’s good for morale.”

“Well, I have some bad news for you. There’s a bit more than her not being a good worker. She’s also been using that bucket of hers to take apples out of my orchard. She started two weeks ago…slowly…but yesterday it got worse. She came in twice, and each time left with a full bucket. Last night I followed her to the inn near the south gate, and found out that’s where she’s selling them.”

“Very well. I’ll have her arrested. As soon as my wife shows up, I’ll have her go out to the pit and take the girl to court.”

The farmer thought for a moment.

“I don’t want to do it that way, Councilman. What I’d prefer is to catch her on my property. Have a guard actually see her stealing the fruit. That way she couldn’t deny anything and we could make an example out of her.”

“True… true. But I’m not going to have a city guard waste time sitting on your orchard waiting over a bucket of apples. We do have other concerns, you know…”

“I’m not asking you to have anyone wait. I know for a fact that she’ll go during the mid-day break. All you have to do is have someone go to my farm just before you let your crew rest. As soon as she shows up and fills the bucket, you’ll have her.”

“Very well. I’ll do as you suggest. And the guard I’ll send will be none other than my wife. I’ll send Anníkki just before I release my workers for the mid-day meal. Assuming your little thief shows up, my wife will handle her appropriately.”

Farmer Orsktackt tightened his lips. “Handle her appropriately…” He had heard stories about the councilman’s wife. Anníkki was a meticulous guard, but had a reputation for cruelty. He saluted his friend and left the work site, beginning to wonder if he was really handling the girl’s stealing in the best way.

* * *

Danka spent a second morning sullenly throwing half-shovels of dirt into waiting wheelbarrows and thinking about her next apple heist. She began to think about strategy; the possibility she could take more than one bucketful at a time, hide the extra apples somewhere, and make two treks to the inn. Another possibility was to obtain or make a large cloth bag and perhaps put more apples in that. Anyhow, that would have to wait…for today she’d still have to content herself with just one bucketful and two coins per trip.

While Danka was thinking about apples, copper coins, and the dress that would change the Path of her Life, the councilman’s wife showed up with her two starving criminals carrying sacks full of food that was not for them. Her husband pointed towards the well and told her about Danka and the plan to catch her. Anníkki cheerfully set off towards the orchard, flexing her switch as she walked.

As soon as she was out of sight, the councilman told the two criminals to take two food rations for themselves before handing out the rest to the workers. He felt sorry for the unfortunate wretches, but did not like confronting his wife on such matters. Without saying anything, the two men ate like ravenous animals.

* * *

Danka ate her mid-day meal with the other workers. Then, as the others lay down to sleep, she grabbed her bucket and set off for the orchard. When she snuck up to the fence, she was pleased to see that no orchard workers were in sight. Excellent. That would make everything so much simpler. She’d grab her apples and sell them, and maybe even have time to relax before the afternoon work shift.

Had she been older and less naïve, Danka would have sensed that something wasn’t right and that she needed to leave immediately. It was too easy, with no one around. Instead of sneaking back and forth with armloads of apples, she simply took the bucket with her and within a couple of minutes had it filled with the best fruit. She hopped the fence and started her trek back to the inn. Her heart stopped when a man in Farmers’ Guild clothing and a city guard stepped onto the road in front of her, blocking her path.

“Good day, little thief! And just where do you think you’re going with my apples?”

Danka panicked. She tried to run, stupidly thinking that she could outpace her pursuers while still holding on to her shovel and apples. It was true that Anníkki could not go after her, because a foot chase was considered unbecoming for a female city guard. However, female guards had the right to order any nearby man to chase and apprehend a criminal, and it was already understood that Farmer Orsktackt would be the one to catch and restrain the thief.

He caught up to her immediately. Danka screamed and threw everything down. The bucket hit the road with a clang and apples rolled all around her. It didn’t help. The farmer grabbed her arm and dragged the struggling girl to where the guard was standing. Danka resisted, incoherently protesting that she was innocent. To her horror, she saw the guard unwinding the leather strips that would be used to tie her hands.

“Take the girl to the fence. Face her to the railing and hold her arms.”

Farmer Orsktackt obeyed, moving his struggling captive to the fence. Danka cried and desperately kicked at his shins while the guard wrapped one of the girl’s wrists with a strip, expertly knotted it, then wrapped the other end around the fence railing. She secured Danka’s other hand. To make sure the thief had no chance of pulling herself free, Anníkki secured her wrists with a second set of ties.

“Pick up the girl’s things and bring them over here. Make sure you get all the apples.”

Danka cried and helplessly pulled against the bindings while Farmer Orsktackt returned to the spot where she had thrown down her things. As soon as he returned, the guard grabbed Danka’s hair and jerked her head back and forth.

“Who is your Master, you dishonored little tart? Who pays for your living?” The guard slapped the prisoner hard across the face. “Tell me, before I break your neck!”

“I… the… the councilman… he…”

“That is correct! And do you know who I am?”

“City… honored… city… guard… Mistress…”

“Yes, a city guard, but I am also the councilman’s wife! Do you understand me? You are in the employ of my husband! You dishonored his name… and the city’s name… and my name… with your vile and loathsome actions!”

“Please Mistress… I didn’t… I… AIEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!”

The guard had picked up her switch and struck a savage blow on the criminal’s thighs, just below her skirt. Danka continued to cry while the guard grabbed her vest and tore it off her shoulders. The fabric was old and gave way easily. The guard then tore at the girl’s skirt, ripping the worn cloth. She produced a small knife and cut the drawstring. She tossed the shredded garment on the ground, next to the ruined vest.

Now wearing nothing but her boots, Danka was shaking with fear, so strongly that her captors could see her body quivering uncontrollably. The sight of a scared naked girl brought out pity in the farmer, but had the opposite effect on the city guard. The guard had worked herself into a sadistic frenzy and seeing the offender helplessly tied to the fence, stripped bare, and paralyzed with fear animated her.

The guard’s next target was Danka’s hair. She roughly pulled at the girl’s braids while she screamed. She landed a very hard slap across the peasant’s face before finishing undoing her hair.

“Now the world sees you for what you are, dishonored tart! You are a loose-haired savage slut!”

The guard picked up her switch and viciously slashed it through the air. Danka screamed from panic while the guard ran her hand up and down her naked bottom.

“Girl-meat. Dishonored girl-meat, meant for my leather. Prepare to suffer, dishonored thieving little tart!”

The guard struck hard as Danka screamed and pulled at her bonds. She twisted and jerked her body, but the bindings held tight and she could not evade the cruel blows. The guard smiled as she tapped Danka’s naked bottom and struck another cruel blow. The crack of leather on bare skin echoed throughout the orchard between the thief’s shrill screams.

Farmer Orsktackt was both fascinated and horrified by the girl’s punishment. Seeing the girl with her hair unbraided was a unique experience, because never had he seen a Danubian woman with her hair loose. The peasant was very attractive and had a nice body, so seeing her aroused him. However, the extent of her suffering, and the knowledge that he was responsible for making it happen, made him sick with guilt. He had not expected the councilman’s wife to tie her to the fence and whip her with the switch on his property, and certainly he had not expected her to undo the thief’s braids.

After 30 hard strokes, the guard paused. Danka has sunk to her knees and was sobbing uncontrollably.

“Very well, you miserable dishonored lying slut… now I’ll let you talk. You sold the apples at the Inn near the south gate, correct?”

The guard concluded her question with a cruel swipe at the girl’s welt-covered backside, crossing multiple weals and eliciting another shrill scream.

“Y… yes… Mistress… I sold… the apples… Inn…”

“For how much?”

“Two copper coins… per… bucket… Mistress…”

“How many coins do you now have?”

“Mistress…Please…AIEEEEEEEEEEE!”

“I’ll ask you again. How many coins do you have?”

“Nineteen… Mistress…”

“Where?”

“Chi… chicken coop… house…. AIEEEEEEEEEEE!”

“Hmm… so your father will be happy to know that his dishonored little slut liar is keeping stolen money on his property! I’ll make sure he knows…”

Danka sobbed, not just from the pain, but from knowing that her dream was gone. Her father would either use the money on Katrínckta or have to return it to Farmer Orsktackt. She screamed when the guard grabbed her hair and pulled her to her feet. The guard struck savagely several more times and Danka sank back to her knees. When the girl’s sobs died down, she continued the interrogation.

“How many times did you steal apples from this orchard?”

“I… I don’t… maybe ten… eleven…”

The guard grabbed Danka’s hair and again jerked her to her feet.

“Yesterday… how many times?”

“Two times, Mistress.”

“What time?”

“Lunchtime… after work, Mistress.”

“Now. Why did you steal the apples? What did you want to do with the money?”

“Buy a dress, Mistress… AIEEEEEEEEEEE!”

“Buy a dress? Why?”

“Go… in town… be nice…”

The guard pulled Danka to her feet yet again and struck hard.

“You miserable dishonored slut… so you wanted to buy a dress to go whoring.”

The guard raised the switch. At that point Danka cared about nothing except trying to avoid any more blows. She sobbed and confessed to something that was blatantly untrue, that she wanted the dress to work as a prostitute. At that point the farmer interjected:

“Guard Anníkki… please. The girl’s confessed. There’s nothing more to be done here. I’m a busy man and I’ve seen enough. I insist you take the criminal to court.”

The guard gave the farmer a disgusted look, angry that he cut short her fun. However, he was right. The girl had confessed and there was no point in interrogating her any further. She untied Danka’s hands from the fence and secured her wrists behind her back. With a firm grip on her arm the guard led her towards the gate and a holding cell inside the city. The farmer, deeply regretting his part in the arrest, reluctantly followed, carrying Danka’s boots and her bucket filled with his apples.

As they approached the gate, a couple of Danka’s neighbors passed by. When the girl tried to put down her head and hide her face under her loose hair, the guard kicked her in the backs of her knees and forced her to kneel. She grabbed the captive’s hair and forced her to look up.

“Tell these men your name and what you did.”

“I… I’m Danka Siluckt… and I… stole apples…”

“She’ll go on the pillory tomorrow. Make sure her family knows, so they can see their daughter’s dishonor.”

Chapter Two – The Dishonored Outcast

In the Grand Duchy of Upper Danubia, all accused criminals had the right to a trial. Serious offenders, people facing either the collar or the death penalty, automatically were assigned a Spokesman. Spokesmen were court employees whose duties included trying to find mitigating circumstances and exculpatory evidence for trial, and then to manage a convicted criminal’s life following the trial. Officially, the Spokesman assumed custody of the criminal after conviction, and worked as their client’s legal protector and mentor.

Petty criminals such as Danka always had a hearing to determine guilt and the circumstances of the crime, but did not have the right to a Spokesman. Their punishment only lasted a single day, thus in theory there wasn’t much at stake, even if a person was wrongly convicted. A day of public humiliation and then release back into the custody of the family – no big deal. The reality was much more complicated, because a person’s life, especially a woman’s life, often was ruined as the result of punishment for a “petty” crime. Danka knew that, with her unsympathetic family, she’d face a hostile reception after her release. She knew that her life would never be the same.

Her trial lasted five minutes. The guard dragged her before a bored local magistrate and explained her crime. Farmer Orsktackt, the trial’s main witness, answered a single question; were the charges against the peasant Danka Siluckt true. He sullenly responded that they were. He was under oath, so he couldn’t say anything else. As much as he wanted to complain about Danka’s treatment and argue that maybe she had been punished enough and should be let go, he never got the chance. He was dismissed and that was the end of his participation in the trial. The sentence was what everyone expected: the peasant Danka Siluckt would spend the night in a holding cell and the next day would spend about eight hours on the pillory. At the end of the day she’d be released into the custody of her family.

A court scribe copied the sentence and Danka’s name onto several sheets of cheap parchment. One copy would be attached to the courthouse door, one attached to the pillory in the city’s plaza, and one delivered to the Siluckt household.

Guard Anníkki led Danka to the holding cell. She untied the prisoner’s hands, but then chained her wrists to the wall. She smiled coldly.

“You may think you were dishonored today, but you weren’t. You haven’t experienced true dishonor. Tomorrow you will. I will humiliate you in a way you never imagined. I will destroy your dignity, and destroy it so thoroughly you’ll never recover. So, sleep well, Danka Siluckt. Tomorrow will be the most horrid day of your life.”

* * *

Farmer Orsktackt went home feeling very disgusted with himself. He couldn’t believe something as simple as dealing with the theft of some apples could turn into such a mess for both his conscience and his reputation. He now felt responsible for the peasant Danka Siluckt, since it was his complaint that got her into so much trouble. He now wished with every bit of his soul that he had never talked to his friend the councilman; that he had just dealt with Danka himself.

Protocol limited Farmer Orsktackt’s options for getting the peasant Danka Siluckt out of the mess he got her into. Since he filed the charge, he could not appeal for clemency, nor in any way be perceived as trying to protect her. But he did have to help Danka if he possibly could. His perception of morality and justice had been violated by his own actions. Somehow he needed to set things straight. He went to bed with his wife, but as soon as she was asleep, he got up, went outside, and spent the night praying to the Lord-Creator for some guidance about how he should handle the following day. The only response he received was a very strong feeling that he needed to be present for the peasant Danka Siluckt’s punishment and bear witness to what was about to happen to her. He received no other insight. So, the next day he rode his horse to the city gate and stabled him at the inn where Danka had sold his apples. He bought a bottle of apple cider and walked into the city. He took a look at the pillory and noted the peasant Danka Siluckt’s punishment declaration. The chains swayed in the wind and two ladders leaned against the frame, in anticipation of the day’s sentence.

“Lord-Creator…what have I done?”

* * *

Danka spent a totally sleepless night. She was terrified of what would happen to her the next day, but she also was extremely uncomfortable. The welts and bruises covering her backside throbbed and made it impossible to sit. However, she couldn’t stand up because the chains restraining her hands were too short. If she lay down, she couldn’t bring her arms down to her sides. She was hungry, and as the night wore on, increasingly thirsty. When the next morning finally came, she was totally exhausted. She waited in terror as it got lighter and lighter outside.

Finally the cell door opened and Guard Anníkki, accompanied by two male assistants, came into the room. One of the men unlocked her chains. He pulled her to her feet and held her roughly while the other tied her hands behind her back. Guard Anníkki said nothing, but her cruel smirk made it obvious that she had not forgotten her threat from last night.

“…the most horrid day of your life.”

Guard Anníkki took charge of the prisoner, firmly grabbing her arm and digging her fingers into Danka’s skin. Danka did not resist. Her terror had subsided into a numb depression and she was physically exhausted from the ordeal of the last 24 hours. The group exited the courthouse and emerged into Rika Heckt-nemat’s main plaza. Already a crowd of curious residents had gathered near the pillory, anticipating the day’s entertainment.

The guard forced Danka to get on her knees while she gave a speech that she had prepared specifically to humiliate her prisoner as much as possible. She mentioned Danka Siluckt’s full name over and over. She talked about Danka’s ridiculous desire to have a dress and to pretend she was something other than what she was: a dishonored menial worker.

One of the male guards pointed a crossbow to her stomach, letting her know that if she resisted, he’d shoot her and she would die an agonizing death. Danka obediently climbed up the ladder when the moment came. The guards secured her wrists and stretched her arms over her shoulders. Tears flowed down the dishonored girl’s cheeks as she felt the ankle irons wrap around her legs and heard the locks click shut. She was completely exposed, with her arms spread over her head and her feet resting on small platforms a half a fathom apart. She felt the chilly morning air blowing between her spread thighs against her exposed vulva. She could feel hundreds of eyes studying her body. Against her will she listened to various comments about her appearance and had to endure a multitude of sexual jokes.

Danka said nothing as the sun rose higher and the air became much warmer. Her arms and legs started cramping from being forced to hold an uncomfortable pose for hours on end, without being able to move. She could move and flex her arms a little, but she couldn’t move her feet. Increasingly her body was protesting against what she was enduring. Her back and shoulders started hurting along with her legs and arms. She thrust her head back and forth and heard the laughter of some of her spectators. She didn’t care. By mid-day the cramping was so unbearable throughout her entire body that she no longer cared about the crowd watching her.

The cathedral bell announced noon and Guard Anníkki called up to her in a tone of feigned sympathy.

“Do you need a break, Danka Siluckt? Would you like something to eat? To drink? You are due a short break, you know…”

“Please Guard Anníkki…”

“Yes, poor girl. We will accommodate you.”

To Danka’s surprise, the male guards actually climbed the ladders and unlocked the pillory’s cuffs. They actually were going to let her down for a while. The men rubbed her shoulders for a few seconds to get the circulation going in her arms. The prisoner was hugely relieved. She knew that the afternoon would be much worse, but for the moment she was on the ground and had the use of her arms and legs. She was horribly thirsty and drank a large cup of cold well-water.

Guard Anníkki waited, ready to play a horrible trick on the culprit. In her hand she held a freshly-baked bread roll. It looked like an innocuous snack, but the bread was full of strong spices that would burn Danka’s mouth as soon as she bit into it. The bread was important for the guard’s plan to totally humiliate the peasant Danka Siluckt and make it impossible for her to ever have a normal life in Rika Heckt-nemat, even as a dishonored day-laborer.

The guard calmly watched as Danka drank he first cup of water. She set down a large pitcher next to the cup before handing her the bread. Danka was so hungry that she took two large bites out of the roll before the burning started in her mouth. The burning quickly became unbearable and Danka instinctively reached for the pitcher. She drank cup after cup of water, desperately trying to calm the fire in her mouth and throat. She drank so much water that her stomach became stretched. As soon as the pitcher was empty, the Guard Anníkki told her companions to grab Danka’s arms and force her back up the ladder. A few seconds later the culprit was restrained spread-eagle, her arms above her head and her feet resting on the two small platforms.

Now the truly horrid part of the worst day of Danka’s life was about to begin. She had a pitcher of water in her stomach, water that very quickly would settle into her bladder. The pressure started building within half-an-hour of her returning to the pillory. The unhappy girl realized that she had been horribly tricked, but there was absolutely nothing she could do about it. Her muscles had started to cramp again, but that discomfort was nothing compared to the agonizing pressure on her bladder. She looked down at the guard, who held up the pitcher and smiled in triumph.

At first Danka thought, that if she put every bit of effort into holding her urine, she’d be able to make it until the end of the day. However, as more and more water seeped into her bladder, she realized that wasn’t going to happen. The cathedral bell struck one. It was just one o’clock. That meant she had three hours to go. No, there was no way she would make it.

The crowd watching her was much larger than it had been in the morning. 2000 residents, a tenth of the city’s entire population, crowded the plaza after having finished their mid-day meal. Danka grit her teeth in a futile effort to avoid pissing in front of all those people. It was no good. The only thing she managed to do was make the rush much worse when it finally came.

Danka sobbed as a torrent of urine poured out of her and splashed on the paving stones at the base of the pillory. The flow was loud and copious, clearly visible to anyone who happened to be watching at that moment. To the Danubians, who were the most fastidious of all the Europeans when it came to that sort of thing, there was no way that Danka possibly could have disgraced herself any worse than relieving herself in front of so many spectators.

The crowd started laughing. The mocking laughter seemed to go on forever, especially when Danka lost control of herself a second time and sent another stream splashing on the pavement. When the laughter died down, the mood of the crowd quickly became much uglier, especially among the women. The spectators whistled low and hissed to express their disapproval at the dishonored criminal. A group of boys ran out the gate and in a few minutes returned with bunches of stinging nettles tied to the ends of long poles. Guard Anníkki nodded her permission and the boys began rubbing the poisonous leaves over Danka’s skin, especially between her legs. As the stinging intensified, she screamed.

By the time the boys tired of tormenting the captive with the nettles, several workmen had brought in wheelbarrows full of sewage and pig manure. They positioned their disgusting cargo in front of the pillory. A group of vagrants who didn’t mind getting their hands dirty picked up handfuls of the sewage and flung it at the hapless criminal. The crowd clapped and whistled their approval every time a handful of excrement hit Danka in the face. By far the worst insults came from the women standing in the crowd. How dare this filthy dishonored slut try to become one of them… how dare she...

The clock struck two. Danka’s punishment still had two hours to go and the crowd was trying to think of something else that would further degrade the pathetic girl chained up in the pillory. Guard Anníkki quietly left the plaza and returned to the courthouse. Her task of ruining Danka Siluckt’s life was now completed, so she saw no point in sticking around. She figured that the crowd might kill the peasant, and if they did, she didn’t want to be present to take any responsibility.

Farmer Orsktackt was completely distressed over the spectacle in the plaza. Already the girl’s life was ruined, but now the spectators, especially the women, had worked themselves into a frenzy. He had seen this happen a couple of times before; the darkest and ugliest side of humanity, the lynch mob. 2000 people had the chance to direct all of their anger and frustration in their lives against a single hapless target, an ignorant peasant girl who had no chance of defending herself. Tightening his lips and cursing himself for having caused the hideous affair, Farmer Orsktackt realized it was up to him to put an end to it and take custody of the criminal. He approached a trio of city guards.

“Listen! I will not have my property and my name dishonored! If you can’t dispose of that criminal with dignity, then I will! Take her down, put her in a wagon, and take her to my property! I’ll deal with her!”

Farmer Orsktackt did not give the guards time to rebuff him. He placed a half-silver piece in each of their hands.

“As you wish, Farmer Orsktackt.”

“Yes, it’s what I wish! Put that girl in a wagon without injuring her, and take her to my property!”

With their cross-bows drawn, the three guards stepped in front of the pillory. They screamed at the crowd to step back, threatening anyone who did not obey with an arrow to the chest. Bewildered and angry at the guards’ sudden change of attitude, the mob pushed backward, murmuring in protest.

Danka was pitiful sight, as she hung limply in her chains and the slime from rotting garbage and sewage dribbled down her body. Her filthy hair covered her face. The guards ordered a servant to bring buckets of water and pour them over the culprit before taking her down, so they wouldn’t dirty themselves too badly when they threw her into the wagon.

Danka was only partially aware of what was going on, but the cold water splashing against her body and over her head brought her back to her senses. Rough hands tightly held her arms to prevent her from falling as the guards un-cuffed her and lowered her to the ground. The guards tied her arms behind her back and dragged her towards the south gate. Her limbs were numb and she could barely move. In spite of her escort’s kicks and threats, she couldn’t get her legs to work. So, two guards carried her, each grabbing her by an arm and by her hair. Some of the spectators wanted to follow, but the guard covering their departure pointed a crossbow at the townsfolk and ordered them to stay back.

“We’re taking her to the river! The show’s over! Go home!”

The guards hoisted Danka into a cart normally used to haul pigs to market. After dumping her face-down on filthy straw and fermented manure, they tied her feet together. They concealed their cargo with a horse blanket and set out for Farmer Orsktackt’s property.

Trying to avoid drawing attention, Farmer Orsktackt picked up Danka’s boots and bucket while everyone else was distracted. He hid both items in a sack and followed the wagon out the gate. Then he got on his horse and rode ahead to his farm.

A few minutes later, three city guards arrived at Farmer Orsktackt’s orchard in a very smelly cart carrying an equally smelly occupant. They untied the girl’s wrists and ankles before dumping her on the ground. They saluted the farmer and returned to the city. The went to the same inn where Danka had sold her stolen fruit, got drunk, and invented a story about how they threw the dishonored apple thief into the Rika Chorna river. They claimed that they had killed a truly evil criminal, because the dishonored girl cried out for the Destroyer Beelzebub to save her before drowning. The men got so drunk and told their version with such convincing detail that they ended up believing it themselves.

Chapter Three – The Fugitive

“Master Tuko. This poor girl…surely you don’t plan to take her to the guest cottage like this…”

“No, Servant Helgakct. I don’t want her in the house until she’s cleaned up. And make sure her hair’s properly braided before I talk to her.”

“As you wish, Master Tuko.”

Servant Helgakct brought a washtub to the front door of the guest cottage and filled it with water, while another servant helped Danka get up and walk to where she would have her bath. Danka sat through her bath in a painful daze, neither cooperating nor resisting as the two servant women bathed her and washed her hair. They decided that she was so dirty that she needed a second bath, and ordered her to stand shivering in the darkness while they dumped and refilled the tub. When they were convinced that Danka was adequately clean, they took her inside and made her sit while they combed and braided her hair. Danka’s new braids were tight and intricately woven; much better the loose careless job her mother always did on her.

Only after Danka was clean and had her hair decently braided did the two women offer anything to eat. She ate a delicious stew with a strange dark brown meat in it. When she asked about the meat, the servants told he she was eating beef. It was the first time in her life she had ever eaten beef. After dinner, on the insistence of the servants, she did something else for the first time: she had to learn how to properly clean her teeth, using a thread and a small brush with salt and water.

Danka was sore, badly bruised, and very tired, but she felt considerably better after her bath and her meal. She had recovered enough to wonder about her situation. She was worried, but no longer terrified. She assumed that had the farmer planned to kill her or harm her in any way, his servants would not have taken the trouble to bathe her and fix her hair.

She looked around the cottage and wondered what she would do about something to wear. There was no clothing anywhere in sight. Her own outfit had been reduced to shreds, so even if she could return to the fence to retrieve it, there wouldn’t be anything remaining that she could put on. She could only hope that someone would bring her some clothes before she had to leave the cottage. When the servants began to clean up and there still was no hint that they were going to bring her anything to wear, she hesitantly asked.

“You will need to speak with the Master about that. He specifically instructed us not to provide you with anything to wear until he has a chance to talk with you. You can cover yourself with that blanket, if you so desire.”

Danka got in bed and pulled the cover over her. She now understood that, until further notice, she had become a prisoner of the orchard owner. A well-treated prisoner, but a prisoner, nonetheless.

“Master Tuko wants you to rest. He will return your items to you tomorrow, but for now, you must rest and recover from today’s ordeal.”

“Yes, Mistress.”

Danka was worried, but fatigue had over-taken her. She was lying in the most comfortable bed she had ever seen, let alone used. She was clean and well-fed. Her muscles ached horribly, so she had no desire to move. She went to sleep.

For the first time in her life, she slept well past sunrise.

* * *

Danka awoke in broad daylight. Servant Helgakct was sitting at the cottage’s table, embroidering a shawl. As soon as she noticed the guest was awake, she summoned a co-worker with a tremendous whistle and handed her the shawl.

Danka badly had to pee. Servant Helgakct pointed towards an outhouse. There still was no hint of any clothing in the cottage, no more than the night before. However, Danka was desperate. She nervously stepped into the bright sunlight and ran to the outhouse. When she finished, she ran back.

“Please Mistress. What am I to do about something to wear?”

“Child, as I told you last night, you must speak with Master Tuko about that. You will have breakfast, and then he will talk to you.”

Danka’s attention was drawn to a plate of eggs, fruit, and bread. A cup of hot liquid sat on the table. It was bitter, but Danka enjoyed it. For the first time in her life she tasted tea.

Servant Helgakct advised the guest to get back in bed and continue resting until the Master came. The peasant girl was still very stiff from the previous day’s ordeal, so she complied. The bright sun came through the door and she could hear the apple pickers singing as they went about their work. Danka wondered… had she simply come to the property a week ago and asked for employment, if Farmer Orsktackt would have given her a job.

As soon his servants finished cleaning up from Danka’s breakfast and took out the dishes, Farmer Orsktackt entered the cottage. Accompanying him was Servant Helgakct, carrying Danka’s bucket filled with apples and her boots. Danka instinctively pulled the cover up to her eyes.

The farmer ordered his employee to return to the house. Then he grabbed a chair and sat next to the bed.

“I’d imagine that you’re wondering why I brought you here, as my guest, since I was the one who set up your arrest. Would you like me to answer that question?”

Trembling, Danka nodded under the blanket.

“Answer me properly, girl. And uncover your face. You are dishonoring yourself by not conversing in a normal manner.”

Tears started rolling down Danka’s cheeks at hearing the word “dishonored”. How could she become any more dishonored than she was already? However, she complied with her host and lowered the blanket to her neck.

“Now speak, if you wish for me to answer your question.”

“Yes… Farmer Orsktackt… why… am I here?”

“I had to bribe three city guards to retrieve you. I didn’t know what else the mob was going to do to you and I didn’t want to find out. So, I paid them to take you out of the city, and here you are. For the moment, you are safe.”

Danka said nothing. She had no idea how she should answer the man who first condemned her and then saved her.

“I want you to understand that what happened to you yesterday was not what I expected. All I wanted was to force you to stop stealing my fruit, and perhaps make an example of you so that others wouldn’t try taking my harvest. I did expect that you’d spend a day on the pillory, but that was all I thought would happen to you. The rest of it, I mean, the crowd, and the way the councilman’s wife treated you, your parents, was not what I intended. I now deeply regret having brought the guards into our affairs. As I said, the only thing I wanted was for you to stop stealing my fruit.”

“I… I apologize about stealing from you, Farmer Orsktackt.”

“The fruit no longer matters. You’ve been punished many times over for your crime. There’s nothing more to be said about that. There’s nothing more to be said about any of your life here. It’s over. The whole town thinks you’re dead. And your parents… you understand that your parents officially disowned you?”

Danka shook her head.

“Answer me properly, girl.”

“They… actually disowned me?”

“Yes, and your father sought the city’s permission to kill you if you ever attempt to return to your family’s property. You’re dishonored, and he doesn’t want that affecting the rest of your household. To enforce the request, the city council lent him a sword.”

Danka stared blankly as tears streamed down her cheeks. A sword. Her own father was planning to kill her just because she no longer was of any use to him. Now she really knew how little her parents thought of her.

“I could never imagine doing such a thing to my children, but I am a rich man and could afford to keep a dishonored relative. I know your family’s situation is different. You’re no longer useful to them, so they need to be rid of you. And… also… to help themselves to the coins you saved, no doubt.”

The farmer continued: “Not that the sword matters. Like everyone else in Rika Heckt-nemat, your father thinks you are dead, that you drowned when the guards threw you in the Rika Chorna. So… your existence as Peasant Siluckt’s daughter has ended. You will leave this city and you will start a new life with a new name somewhere else. I am returning your bucket to you, filled with fresh apples. I put a note in there explaining that I gave them to you, if any guard stops you. I had my seamstress clean and repair your boots. Tonight, after you have rested and recovered, you will walk out the east gate of my farm, follow the path that keeps you away from the road, and you will keep going until you’ve eaten all of your apples.”

“I… I’m grateful… I mean… that you saved me… and that you want to help me… but I don’t understand, Farmer Orsktackt. I’m just a dishonored thief. I’m nothing now, not even a well-digger. I dishonored myself on your land, and I wanted to steal from you as much as I could. Why are you helping me?”

“I have my reasons. Part of it is my eldest daughter is almost your age. Next month my wife will braid her hair for the first time. She will have a nice celebration and I will present her with a fine dress. The neighbor’s boy is interested in her, so, I presume, after her hair is braided and she has her dress, I will allow him to court her. In other words, she’ll have all the things you wanted. That’s important, because when I saw you tied to the fence, and later on the pillory, I imagined how, with nothing more than a change in the Path in Life; that could have been my own daughter, and not you.

“There’s more. Some of it I can explain to you, and some of it I couldn’t explain to anyone. As an archer in the Grand Duke’s battalion, I did things… I mean… we all did, that each of us will have to answer for on the day we hold up our mirrors before the Lord-Creator. I can’t change any of that. Now, you have become another part of the Path of my Life that I must justify when I hold up my mirror. You are a thief, but you had your reasons to do what you did, and I don’t believe your soul is broken. I don’t want to be responsible for your death. I want you to live. I want you to leave this city, find a new Path in Life, and prosper. So, I will provide what you need to safely escape. What becomes of you after your escape will be the result of your own decisions.”

Danka wondered how, as a young woman travelling alone, she could possibly go anywhere. She had never been any further from her house than the city market, the town cathedral, and her work site. She hadn’t even gone as far as the northern or western districts of Rika Heckt-nemat, nor had she ever seen the Rika Chorna, which now flowed to the north of the city.

The farmer was wondering the same thing. How on earth would the ignorant girl sitting in front of him ever be able to fend for herself? Well, she’d just have to. Whatever fate awaited Danka, he had to send her on her way and see to it that she never came back. Neither he nor the girl had any choice. She’d have to leave, and that departure needed to be as soon as possible.

None of the townsfolk could know that she was still alive, nor could anyone find out that he had rescued her. If his neighbors realized he was sheltering a criminal, and above all a criminal who had stolen from him, he’d be dishonored and expelled from the Farmer’s Guild. It wasn’t just Danka’s life at stake, nor just his own. He also had his family and the Guild to think about.

Farmer Tuko Orsktackt had traveled across the entire Duchy, first with the Duke’s archers’ battalion and later to buy supplies and tools for his farm. He was well aware that a lone peasant girl was an easy target for every rapist, slaver, and brigand travelling the road. He dared not give her any money, nor any decent clothing, because such things would make her worth killing. The land-owner could think of only one way Danka could get away from Rika Heckt-nemat and survive long enough to establish a new life somewhere else.

It was a completely dishonorable solution, but one that would be very effective. The Farmers’ Guild had an important secret that its members occasionally used when they needed to move gold or diamonds from one city to another. It was a fake Public Penance collar. By the mid-1700’s the Danubian Church already had re-introduced the pre-Christian method of performing Public Penance, in which a person who wanted to atone for sin humiliated himself by surrendering his clothing and anything else that could be worn. Instead of clothing, the sinner wore a metal collar that marked him as being in the custody of and protected by the Danubian Church. A person wearing a Church collar was prohibited from wearing anything else.

Brigands avoided persons performing Public Penance because they never had anything on them worth stealing. Anyone touching a woman performing Penance would be forever condemned by the Lord-Creator to the Hell-Fire, and the worldly punishment for such an offence was crucifixion. Danubian society took Public Penance very seriously, which meant that anyone performing it was protected by a multitude of taboos and the full authority of the Church. A person wearing a Church collar was completely safe almost anywhere.

Tuko Orsktackt had, in his possession, a fake Church collar that could be unlatched and taken off as easily as any necklace. It had been made for him several years before by a Guild artisan and its purpose was to disguise him while he was travelling with large amounts of the Guild’s money. In theory the collar was an accountable item that the other Guild members could demand to see at any time. However, Tuko had a dispute with two other Guild farmers the previous year and now someone else was tasked with carrying the group’s coins. Tuko’s replacement had his own collar, so it seemed that the Guild had forgotten about the one still in his possession.

There was some risk involved, but Farmer Orsktackt calculated he could give his collar to Danka. That would allow her to freely travel the roads, with everyone assuming she enjoyed Church protection.

“Girl, you haven’t been anywhere. Not even as far as the top of the nearest hill, I presume?”

“No, Farmer Orsktackt.”

“So the journey that you face frightens you. Is that not so?”

“Yes, Farmer Orsktackt.”

“I’m worried about it as well. I’d accompany you if I could, but I can’t. There is only one thing I can do for you, and that is to provide you with a disguise that will grant you safety as you travel.”

Tuko placed the collar in Danka’s hands. “Not even my family or my servants know I have this. You must not let anyone see it until nightfall. Never… never! let anyone see you putting it on or taking it off.”

“But… Farmer Orsktackt, this is all you’re giving me? I can’t…”

“You may think you can’t, but you have no choice. If you go out on the road, by yourself, wearing anything but this collar, you’ll be dead or enslaved by the end of the day. It’s safe passage for you. It comes with a heavy price, but it’s safe passage.”

Tuko explained how the collar worked and even divulged its purpose, to disguise Guild members when they were transporting large sums of money. Tuko hated betraying a Guild secret to a peasant, but he felt that it was necessary for Danka to understand how important the collar was and the sacrifice he was making by entrusting it to her. The collar was an extremely valuable item that had to be treated with great care. It could not be replaced.

“You’ll have to go to the mirror and try out the collar. Practice putting it on and taking it off. Then you’ll need to practice putting it on and taking it off without looking. When you’re crouching outside a city gate or hiding behind a tree, you won’t have the benefit of using your reflection.”

Danka reluctantly pushed aside the blanket. Given her circumstances, trying to display modesty around Farmer Orsktackt was not possible. Anyway, he already had seen her figure in its entirety, so there was nothing more to hide from him. She stood up, positioned herself in front of the mirror, and started fiddling with the collar mechanism. She realized that Farmer Orsktackt was studying the welts on her backside, but she tried to ignore him.

Danka was surprised and fascinated by her reflection. She was pleased by how sophisticated she looked, now that her hair was braided by a woman who actually cared about doing it properly. The young peasant also realized how much she looked like her sister. As much as her mother kept calling Katrínckta “the pretty one”, actually the two daughters were almost identical.

Danka practiced with the collar a couple of times; then turned away from the mirror to practice using touch only. The farmer nodded approvingly when she completed that task.

“There’s another thing you must know before you leave. Can you read?”

Danka blushed and twisted her hands.

“Answer me, girl. Can you read?”

“No, Farmer Orsktackt.”

“Well, there’s no time to teach you how to read, but you are going to have to learn the alphabet so you can recognize letters. Maybe it’s something you can practice whenever you’re sitting alone and have nothing else to do. I’ll have my servants’ tutor instruct you. Put the collar away. Don’t let her see it.”

Danka spent the next several hours learning how to copy and draw letters. She discovered the mystery of all those strange lines, that each shape represented a sound. She was quick to memorize the alphabet and remember which sound each letter corresponded to. The tutor regretted not being able to spend more time with Danka, because it was obvious the girl could have been taught to read within a few weeks.

Farmer Orsktackt returned with troubling news. The guards’ story about her calling out to Beelzebub just before she drowned had made its way through Rika Heckt-nemat’s population. Suddenly everyone was very worried that her corpse had not been seen floating in the Rika Chorna. The city was in a panic about it, with guards and volunteers searching the shore downstream for any trace of Danka’s body, just to verify that she was indeed dead and that Beelzebub had not rescued her.

“I was going to suggest you follow the river to Danúbikt Móskt to see if you could get a job there. Now you can’t go that way, because several hundred people are looking for you. You’ll have to go east, upstream, towards the mountains.”